STAMP DUTY -IMPOSED ON AMERICA

ON 1755 NOVEMBER 1 FOR MILITARY EXPENSES OBJECTED GREATLY -REPEALED 1766

Background[edit]

The British victory in the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), known in America as the French and Indian War, had been won only at a great financial cost. During the war, the British national debt increased more than four fold, rising from £72,289,673 (equal to £10.1 billion today) to almost £329,586,789 by 1764 (equal to £42 billion today).[7] Post-war expenses were expected to remain high because the Bute ministry decided in early 1763 to keep ten thousand British regular soldiers in the American colonies, which would cost about £225,000 per year, equal to £30 million today.[8]

The primary reason for retaining such a large force was that demobilizing the army would put 1,500 officers out of work, many of whom were well-connected in Parliament.[9] This made it politically prudent to retain a large peacetime establishment, but Britons were averse to maintaining a standing army at home so it was necessary to garrison most of the troops elsewhere.[10]

George Grenville became prime minister in April 1763 after the failure of the short-lived Bute Ministry, and he had to find a way to pay for this large peacetime army. Raising taxes in Britain was out of the question, since there had been virulent protests in England against the Bute ministry's 1763 cider tax, with Bute being hanged in effigy.[14] The Grenville ministry therefore decided that Parliament would raise this revenue by taxing the American colonists without their consent. This was something new; Parliament had previously passed measures to regulate trade in the colonies, but it had never before directly taxed the colonies to raise revenue.[15]

| |

| Long title | An act for granting and applying certain stamp duties, and other duties, in the British colonies and plantations in America, towards further defraying the expenses of defending, protecting, and securing the same; and for amending such parts of the several acts of parliament relating to the trade and revenues of the said colonies and plantations, as direct the manner of determining and recovering the penalties and forfeitures therein mentioned. |

|---|---|

| Citation | 5 George III, c. 12 |

| Introduced by | The Rt. Hon. George Grenville, MP Prime Minister, Chancellor of the Exchequer & Leader of the House of Commons |

| Territorial extent | |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 22 March 1765 |

| Commencement | 1 November 1765 |

| Repealed | 18 March 1766 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | Act Repealing the Stamp Act 1766 |

| Relates to | Declaratory Act |

Status: Repealed

| |

So long as this sort of help was forthcoming, there was little reason for the British Parliament to impose its own taxes on the colonists. But after the peace of 1763, colonial militias were quickly stood down. Militia officers were tired of the disdain shown to them by regular British officers, and were frustrated by the near-impossibility of obtaining regular British commissions; they were unwilling to remain in service once the war was over. In any case, they had no military role, as the Indian threat was minimal and there was no foreign threat. Colonial legislators saw no need for the British troops.

Prime Minister George Grenville

The Sugar Act of 1764 was the first tax in Grenville's program to raise a revenue in America, which was a modification of the Molasses Act of 1733. The Molasses Act had imposed a tax of 6 pence per gallon (equal to £3.74 today) on foreign molasses imported into British colonies. The purpose of the Molasses Act was not actually to raise revenue, but instead to make foreign molasses so expensive that it effectively gave a monopoly to molasses imported from the British West Indies.[16]

American colonists initially objected to the Sugar Act for economic reasons, but before long they recognized that there were constitutional issues involved.[20] The British Constitution guaranteed that British subjects could not be taxed without their consent, which came in the form of representation in Parliament. The colonists elected no members of Parliament, and so it was seen as a violation of the British Constitution for Parliament to tax them. There was little time to raise this issue in response to the Sugar Act, but it came to be a major objection to the Stamp Act the following year.

Details of tax[edit]

The Stamp Act was passed by Parliament on March 22, 1765 with an effective date of November 1, 1765. It passed 205–49 in the House of Commons and unanimously in the House of Lords.[28] Historians Edmund and Helen Morgan describe the specifics of the tax:

The high taxes on lawyers and college students were designed to limit the growth of a professional class in the colonies.[30] The stamps had to be purchased with hard currency, which was scarce, rather than the more plentiful colonial paper currency. To avoid draining currency out of the colonies, the revenues were to be expended in America, especially for supplies and salaries of British Army units who were stationed there.[31]

Two features of the Stamp Act involving the courts attracted special attention. The tax on court documents specifically included courts "exercising ecclesiastical jurisdiction." These type of courts did not currently exist in the colonies and no bishops were currently assigned to the colonies, who would preside over the courts. Many colonists or their ancestors had fled England specifically to escape the influence and power of such state-sanctioned religious institutions, and they feared that this was the first step to reinstating the old ways in the colonies. Some Anglicans in the northern colonies were already openly advocating the appointment of such bishops, but they were opposed by both southern Anglicans and the non-Anglicans who made up the majority in the northern colonies.[32]

The Stamp Act allowed admiralty courts to have jurisdiction for trying violators, following the example established by the Sugar Act. However, admiralty courts had traditionally been limited to cases involving the high seas. The Sugar Act seemed to fall within this precedent, but the Stamp Act did not, and the colonists saw this as a further attempt to replace their local courts with courts controlled by England.[33]

Protests in the streets[edit]

Whether stimulated externally or ignited internally, ferment during the years from 1761 to 1766 changed the dynamics of social and political relations in the colonies and set in motion currents of reformist sentiment with the force of a mountain wind. Critical to this half decade was the colonial response to England’s Stamp Act, more the reaction of common colonists than that of their presumed leaders.[48]

Both loyal supporters of English authority and well-established colonial protest leaders underestimated the self-activating capacity of ordinary colonists. By the end of 1765 … people in the streets had astounded, dismayed, and frightened their social superiors.[49]

Massachusetts[edit]

Early street protests were most notable in Boston. Andrew Oliver was a distributor of stamps for Massachusetts who was hanged in effigy on August 14, 1765 "from a giant elm tree at the crossing of Essex and Orange Streets in the city’s South End." Also hung was a Jack boot painted green on the bottom ("a Green-ville sole"), a pun on both Grenville and the Earl of Bute, the two people most blamed by the colonists. Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson ordered sheriff Stephen Greenleaf to take down the effigy, but he was opposed by a large crowd. All day the crowd detoured merchants on Orange Street to have their goods symbolically stamped under the elm tree, which later became known as the "Liberty Tree".

American newspapers reacted to the Stamp Act with anger and predictions of the demise of journalism.

Ebenezer MacIntosh was a veteran of the Seven Years' War and a shoemaker. One night, he led a crowd which cut down the effigy of Andrew Oliver and took it in a funeral procession to the Town House where the legislature met. From there, they went to Oliver's office—which they tore down and symbolically stamped the timbers. Next, they took the effigy to Oliver’s home at the foot of Fort Hill, where they beheaded it and then burned it—along with Oliver’s stable house and coach and chaise. Greenleaf and Hutchinson were stoned when they tried to stop the mob, which then looted and destroyed the contents of Oliver's house. Oliver asked to be relieved of his duties the next day.[50] This resignation, however, was not enough. Oliver was ultimately forced by MacIntosh to be paraded through the streets and to publicly resign under the Liberty Tree.[51]As news spread of the reasons for Andrew Oliver's resignation, violence and threats of aggressive acts increased throughout the colonies, as did organized groups of resistance. Throughout the colonies, members of the middle and upper classes of society formed the foundation for these groups of resistance and soon called themselves the Sons of Liberty. These colonial groups of resistance burned effigies of royal officials, forced Stamp Act collectors to resign, and were able to get businessmen and judges to go about without using the proper stamps demanded by Parliament.[52]

On August 26, MacIntosh led an attack on Hutchinson's mansion. The mob evicted the family, destroyed the furniture, tore down the interior walls, emptied the wine cellar, scattered Hutchinson's collection of Massachusetts historical papers, and pulled down the building's cupola. Hutchinson had been in public office for three decades; he estimated his loss at £2,218[53] (in today's money, at nearly $250,000). Nash concludes that this attack was more than just a reaction to the Stamp Act:

But it is clear that the crowd was giving vent to years of resentment at the accumulation of wealth and power by the haughty prerogative faction led by Hutchinson. Behind every swing of the ax and every hurled stone, behind every shattered crystal goblet and splintered mahogany chair, lay the fury of a plain Bostonian who had read or heard the repeated references to impoverished people as "rable" and to Boston’s popular caucus, led by Samuel Adams, as a "herd of fools, tools, and synchophants."[54]

Governor Francis Bernard offered a £300 reward for information on the leaders of the mob, but no information was forthcoming. MacIntosh and several others were arrested, but were either freed by pressure from the merchants or released by mob action.[55]

The street demonstrations originated from the efforts of respectable public leaders such as James Otis, who commanded the Boston Gazette, and Samuel Adams of the "Loyal Nine" of the Boston Caucus, an organization of Boston merchants. They made efforts to control the people below them on the economic and social scale, but they were often unsuccessful in maintaining a delicate balance between mass demonstrations and riots. These men needed the support of the working class, but also had to establish the legitimacy of their actions to have their protests to England taken seriously.[56] At the time of these protests, the Loyal Nine was more of a social club with political interests but, by December 1765, it began issuing statements as the Sons of Liberty.[57]

Rhode Island[edit]

Rhode Island also experienced street violence. A crowd built a gallows near the Town House in Newport on August 27, where they carried effigies of three officials appointed as stamp distributors: Augustus Johnson, Dr. Thomas Moffat, and lawyer Martin Howard. The crowd at first was led by merchants William Ellery, Samuel Vernon, and Robert Crook, but they soon lost control. That night, the crowd was led by a poor man named John Weber, and they attacked the houses of Moffat and Howard, where they destroyed walls, fences, art, furniture, and wine. The local Sons of Liberty were publicly opposed to violence, and they refused at first to support Weber when he was arrested. They were persuaded to come to his assistance, however, when retaliation was threatened against their own homes. Weber was released and faded into obscurity.[58]

Howard became the only prominent American to publicly support the Stamp Act in his pamphlet "A Colonist's Defence of Taxation" (1765). After the riots, Howard had to leave the colony, but he was rewarded by the Crown with an appointment as Chief Justice of North Carolina at a salary of ₤1,000.[59]

New York[edit]

Main article: Province of New York § Stamp Act

In New York, James McEvers resigned his distributorship four days after the attack on Hutchinson's house. The stamps arrived in New York Harbor on October 24 for several of the northern colonies. Placards appeared throughout the city warning that "the first man that either distributes or makes use of stamped paper let him take care of his house, person, and effects." New York merchants met on October 31 and agreed not to sell any English goods until the Act was repealed. Crowds took to the streets for four days of demonstrations, uncontrolled by the local leaders, culminating in an attack by two thousand people on Governor Cadwallader Colden's home and the burning of two sleighs and a coach. Unrest in New York City continued through the end of the year, and the local Sons of Liberty had difficulty in controlling crowd actions.[60]

Other Colonies[edit]

In Frederick Maryland, a court of 12 magistrates ruled the Stamp Act invalid on November 23, 1765 and directed that businesses and colonial officials proceed in all matters without use of the stamps. A week later, a crowd conducted a mock funeral procession for the act in the streets of Frederick. The magistrates have been dubbed the "12 Immortal Justices," and November 23 has been designated "Repudiation Day" by the Maryland state legislature. On October 1, 2015, Senator Cardin (D-MD) read into the Congressional Record a statement noting 2015 as the 250th anniversary of the event. Among the 12 magistrates was William Luckett, who later served as Lieutenant Colonel in the Maryland Militia at the battle of Germantown.

Other popular demonstrations occurred in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Annapolis, Maryland, Wilmington and New Bern, North Carolina, and Charleston, South Carolina. In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, demonstrations were subdued but even targeted Benjamin Franklin's home, although it was not vandalized.[61] By November 16, twelve of the stamp distributors had resigned. The Georgia distributor did not arrive in America until January 1766, but his first and only official action was to resign.[62]

The overall effect of these protests was to both anger and unite the American people like never before. Opposition to the Act inspired both political and constitutional forms of literature throughout the colonies, strengthened the colonial political perception and involvement, and created new forms of organized resistance. These organized groups quickly learned that they could force royal officials to resign by employing violent measures and threats.[63]

Quebec, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and the Caribbean[edit]

The main issue was constitutional rights of Englishmen, so the French in Quebec did not react. Some English-speaking merchants were opposed, but were in a fairly small minority. The Quebec Gazette ceased publication until the act was repealed, apparently over the unwillingness to use stamped paper.[64] In neighboring Nova Scotia a number of former New England residents objected, but recent British immigrants and London-oriented business interests based in Halifax, the provincial capital were more influential. The only major public protest was the hanging in effigy of the stamp distributor and Lord Bute. The act was implemented in both provinces, but Nova Scotia's stamp distributor resigned in January 1766, beset by ungrounded fears for his safety. Authorities there were ordered to allow ships bearing unstamped papers to enter its ports, and business continued unabated after the distributors ran out of stamps.[65] The Act occasioned some protests in Newfoundland, and the drafting of petitions opposing not only the Stamp Act, but the existence of the customhouse at St. John's, based on legislation dating back to the reign of Edward VI forbidding any sort of duties on the importation of goods related to its fisheries.[66]

Violent protests were few in the Caribbean colonies. Political opposition was expressed in a number of colonies, including Barbados and Antigua, and by absentee landowners living in Britain. The worst political violence took place on St. Kitts and Nevis. Riots took place on October 31, 1765, and again on November 5, targeting the homes and offices of stamp distributors; the number of participants suggests that the percentage of St. Kitts' white population involved matched that of Bostonian involvement in its riots. The delivery of stamps to St. Kitts was successfully blocked, and they were never used there. Montserrat and Antigua also succeeded in avoiding the use of stamps; some correspondents thought that rioting was prevented in Antigua only by the large troop presence. Despite vocal political opposition, Barbados used the stamps, to the pleasure of King George. In Jamaica there was also vocal opposition, which included threats of violence. There was much evasion of the stamps, and ships arriving without stamped papers were allowed to enter port. Despite this, Jamaica produced more stamp revenue (£2,000) than any other colony.[67]

Sons of Liberty[edit]

Main article: Sons of Liberty

It was during this time of street demonstrations that locally organized groups started to merge into an inter-colonial organization of a type not previously seen in the colonies. The term "sons of liberty" had been used in a generic fashion well before 1765, but it was only around February 1766 that its influence extended throughout the colonies as an organized group using the formal name "Sons of Liberty", leading to a pattern for future resistance to the British that carried the colonies towards 1776.[68] Historian John C. Miller noted that the name was adopted as a result of Barre's use of the term in his February 1765 speech.[69]

The organization spread month by month after independent starts in several different colonies. By November 6, a committee was set up in New York to correspond with other colonies, and in December an alliance was formed between groups in New York and Connecticut. In January, a correspondence link was established between Boston and Manhattan, and by March, Providence had initiated connections with New York, New Hampshire, and Newport. By March, Sons of Liberty organizations had been established in New Jersey, Maryland, and Norfolk, Virginia, and a local group established in North Carolina was attracting interest in South Carolina and Georgia.[70]

The officers and leaders of the Sons of Liberty "were drawn almost entirely from the middle and upper ranks of colonial society," but they recognized the need to expand their power base to include "the whole of political society, involving all of its social or economic subdivisions." To do this, the Sons of Liberty relied on large public demonstrations to expand their base.[71] They learned early on that controlling such crowds was problematical, although they strived to control "the possible violence of extra-legal gatherings." The organization professed its loyalty to both local and British established government, but possible military action as a defensive measure was always part of their considerations. Throughout the Stamp Act Crisis, the Sons of Liberty professed continued loyalty to the King because they maintained a "fundamental confidence" that Parliament would do the right thing and repeal the tax.[72]

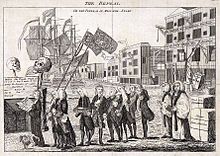

A British newspaper cartoon reacts to the repeal of the Stamp Act.

Colonial newspapers were a major source of public unrest after the passage of the Stamp Act. Some of the earliest forms of American propaganda appeared in these printings in response to the law. The articles written in colonial newspapers were particularly critical of the act because of the Stamp Act's disproportionate effect on printers. David Ramsay, a patriot and historian from South Carolina, wrote of this phenomenon shortly after the American Revolution:

It was fortunate for the liberties of America, that newspapers were the subject of a heavy stamp duty. Printers, when influenced by government, have genereally arranged themselves on the side of liberty, nor are they less remarkable for attention to the profits of their profession. A stamp duty, which openly invaded the first, and threatened a great diminution of the last, provoked their united zealous opposition.[73]

Most printers were critical of the Stamp Act, although a few Loyalist voices did exist. Some of the more subtle Loyalist sentiments can be seen in publications such as The Boston Evening Post, which was run by British sympathizers John and Thomas Fleet. The article detailed a violent protest that occurred in New York in December, 1765, then described the riot's participants as "imperfect" and labeled the group's ideas as "contrary to the general sense of the people."[74] These Loyalists beliefs can be seen in some of the early newspaper articles about the Stamp Act, but the anti-British writings were more prevalent and seem to have had a more powerful effect.[75]

Many papers assumed a relatively conservative tone before the act went into effect, implying that they might close if it wasn't repealed. However, as time passed and violent demonstrations ensued, the authors became more vitriolic. Several newspaper editors were involved with the Sons of Liberty, such as William Bradford of The Pennsylvania Journal and Benjamin Edes of The Boston Gazette, and they echoed the group's sentiments in their publications.[76] The Stamp Act went into effect that November, and many newspapers ran editions with imagery of tombstones and skeletons, emphasizing that their papers were "dead" and would no longer be able to print because of the Stamp Act.[77] However, most of them returned in the upcoming months, defiantly appearing without the stamp of approval that was deemed necessary by the Stamp Act. Printers were greatly relieved when the law was nullified in the following spring, and the repeal asserted their positions as a powerful voice (and compass) for public opinion.[78]

Stamp Act Congress[edit]

Main article: Stamp Act Congress

The Stamp Act Congress was held in New York in October 1765. Twenty-seven delegates from nine colonies were the members of the Congress, and their responsibility was to draft a set of formal petitions stating why Parliament had no right to tax them.[79] Among the delegates were many important men in the colonies. Historian John Miller observes, "The composition of this Stamp Act Congress ought to have been convincing proof to the British government that resistance to parliamentary taxation was by no means confined to the riffraff of colonial seaports."[80]

The youngest delegate was 26-year-old John Rutledge of South Carolina, and the oldest was 65-year-old Hendrick Fisher of New Jersey. Ten of the delegates were lawyers, ten were merchants, and seven were planters or land-owning farmers; all had served in some type of elective office, and all but three were born in the colonies. Four died before the colonies declared independence, and four signed the Declaration of Independence; nine attended the first and second Continental Congresses, and three were Loyalists during the Revolution.[81]

New Hampshire declined to send delegates, and North Carolina, Georgia, and Virginia were not represented because their governors did not call their legislatures into session, thus preventing the selection of delegates. Despite the composition of the congress, each of the Thirteen Colonies eventually affirmed its decisions.[82] Six of the nine colonies represented at the Congress agreed to sign the petitions to the King and Parliament produced by the Congress. The delegations from New York, Connecticut, and South Carolina were prohibited from signing any documents without first receiving approval from the colonial assemblies that had appointed them.[83]

Massachusetts governor Francis Bernard believed that his colony’s delegates to the Congress would be supportive of Parliament. Timothy Ruggles in particular was Bernard's man, and was elected chairman of the Congress. Ruggles' instructions from Bernard were to "recommend submission to the Stamp Act until Parliament could be persuaded to repeal it."[84] Many delegates felt that a final resolution of the Stamp Act would actually bring Britain and the colonies closer together. Robert Livingston of New York stressed the importance of removing the Stamp Act from the public debate, writing to his colony's agent in England, "If I really wished to see America in a state of independence I should desire as one of the most effectual means to that end that the stamp act should be enforced."[85]

Declaration of Rights and Grievances

The Congress met for 12 consecutive days, including Sundays. There was no audience at the meetings, and no information was released about the deliberations.[86] The meeting's final product was called "The Declaration of Rights and Grievances", and was drawn up by delegate John Dickinson of Pennsylvania. This Declaration raised fourteen points of colonial protest. It asserted that colonists possessed all the rights of Englishmen in addition to protesting the Stamp Act issue, and that Parliament could not represent the colonists since they had no voting rights over Parliament. Only the colonial assemblies had a right to tax the colonies. They also asserted that the extension of authority of the admiralty courts to non-naval matters represented an abuse of power.[87]

In addition to simply arguing for their rights as Englishmen, the congress also asserted that they had certain natural rights solely because they were human beings. Resolution 3 stated, "That it is inseparably essential to the freedom of a people, and the undoubted right of Englishmen, that no taxes be imposed on them, but with their own consent, given personally, or by their representatives." Both Massachusetts and Pennsylvania brought forth the issue in separate resolutions even more directly when they respectively referred to "the Natural rights of Mankind" and "the common rights of mankind".[88]

Christopher Gadsden of South Carolina had proposed that the Congress' petition should go only to the king, since the rights of the colonies did not originate with Parliament. This radical proposal went too far for most delegates and was rejected. The "Declaration of Rights and Grievances" was duly sent to the king, and petitions were also sent to both Houses of Parliament.[89]

Repeal[edit]

Grenville was replaced by Lord Rockingham as Prime Minister on July 10, 1765. News of the mob violence began to reach England in October. Conflicting sentiments were taking hold in Britain at the same time that resistance was building and accelerating in America. Some wanted to strictly enforce the Stamp Act over colonial resistance, wary of the precedent that would be set by backing down.[90] Others felt the economic effects of reduced trade with America after the Sugar Act and an inability to collect debts while the colonial economy suffered, and they began to lobby for a repeal of the Stamp Act.[91] A significant part of colonial protest had included various non-importation agreements among merchants who recognized that a significant portion of British industry and commerce was dependent on the colonial market. This movement had spread through the colonies with a significant base coming from New York City, where 200 merchants had met and agreed to import nothing from England until the Stamp Act was repealed.[92]

This cartoon depicts the repeal of the Stamp Act as a funeral, with Grenville carrying a child's coffin marked "born 1765, died 1766".

William Pitt stated in the Parliamentary debate that everything done by the Grenville ministry with respect to the colonies "has been entirely wrong." He further stated, "It is my opinion that this Kingdom has no right to lay a tax upon the colonies." Pitt still maintained "the authority of this kingdom over the colonies, to be sovereign and supreme, in every circumstance of government and legislature whatsoever," but he made the distinction that taxes were not part of governing, but were "a voluntary gift and grant of the Commons alone." He rejected the notion of virtual representation, as "the most contemptible idea that ever entered into the head of man."[94]

Grenville responded to Pitt:

Protection and obedience are reciprocal. Great Britain protects America; America is bound to yield obedience. If, not, tell me when the Americans were emancipated? When they want the protection of this kingdom, they are always ready to ask for it. That protection has always been afforded them in the most full and ample manner. The nation has run itself into an immense debt to give them their protection; and now they are called upon to contribute a small share towards the public expence, and expence arising from themselves, they renounce your authority, insult your officers, and break out, I might also say, into open rebellion.[95]

Pitt’s response to Grenville included, "I rejoice that America has resisted. Three millions of people, so dead to all the feelings of liberty as voluntarily to submit to be slaves, would have been fit instruments to make slaves of the rest."[96]

Between January 17 and 27, Rockingham shifted the attention from constitutional arguments to economic by presenting petitions from all over the country complaining of the economic repercussions felt throughout the country. On February 7, the House of Commons rejected a resolution, saying that it would back the King in enforcing the Act by 274–134. Henry Seymour Conway, the government's leader in the House of Commons, introduced the Declaratory Act in an attempt to address both the constitutional and the economic issues, which affirmed the right of Parliament to legislate for the colonies "in all cases whatsoever", while admitting the inexpediency of attempting to enforce the Stamp Act. Only Pitt and three or four others voted against it. Other resolutions did pass which condemned the riots and demanded compensation from the colonies for those who suffered losses because of the actions of the mobs.[97]

On February 21, a resolution to repeal the Stamp Act was introduced and passed by a vote of 276–168. The King gave royal assent on March 18, 1766.[98][99]

No comments:

Post a Comment