Maharani Jindan Kaur Emerald and Seed-Pearl Necklace

Origin of Name :-

The name refers to an historic emerald and seed-pearl necklace that once belonged to Maharani Jindan Kaur, the 9th and last regular wife of Maharajah Ranjeet Singh, "The Lion of the Punjab," whose empire extended from the Indian Ocean to the Himalayas. The necklace was actually a gift by Maharajah Ranjeet Singh to his young and pretty 18-year old wife Jindan Kaur, whom he took as his 9th and last regular wife in 1835, and who bore him his last son Duleep Singh, just 10 months before his death in 1839. In the uncertain conditions that prevailed soon after his death, Ranjeet Singh's two eldest sons Kharak Singh and Sher Singh succeeded one after another, but their reign was short-lived as both of them were assassinated. Finally, Duleep Singh was proclaimed as Maharajah in 1843 at the age of five years, with his mother Maharani Jindan Kaur as Regent, and his maternal uncle as Prime Minister. However, after sometime the Prime Minister was also assassinated, and Maharani Jindan Kaur took power as the absolute monarch of the still independent Punjab with the support of the army, bordered in the south by the British Indian Empire, and ruling in the name of her son Maharajah Duleep Singh.

| Share this page: | |||

| Tumblr | |||

The British who had hitherto not annexed Punjab to their ever widening empire, took advantage of the instability created by Ranjeet Singh's death, and attacked the Punjab, at the time of Jindan Kaur's regency. Jindan Kaur mobilized a vast army against the British, and waged two wars, the first and second Anglo-Sikh wars between 1846 and 1849. However, both wars were unsuccessful, and eventually led to the annexation of the Punjab to the British Raj in 1849. Maharani Jindan Kaur posed a serious challenge to the British in Punjab, because of her large following, and her ability to organize resistance and plot rebellions against them. Thus they were forced to keep her under incarceration in different prisons, until her dramatic escape to Nepal in 1849, where she was given asylum by the King of Nepal. Thus, Jindan Kaur, the last wife of the "Lion of Punjab" Maharajah Ranjeet Singh, proved to be a worthy successor to her illustrious husband, safeguarding the interests of the people of Punjab, in spite of her incarceration and subsequent exile in Nepal and London, until her death in 1863. Maharani Jindan Kaur may quite appropriately be referred to as the "Lioness of Punjab" for the consistent anti-British policies she adopted throughout her life, until her death in Britain, the land of her sworn enemy.

Thus, the Emerald and Seed-Pearl Necklace, has gone down in history, as a piece of jewelry that had adorned the neck of a brave queen who had dared challenge the might of the British Empire, and fought consistently to safeguard the cultural, religious and other interests of her people throughout her life.

Characteristics of the necklace

The Maharani Jindan Kaur Emerald and Pearl Necklace appears at a Bonhams auction, 146 years after the death of Maharani Jindan Kaur in 1863.

The Maharani Jindan Kaur Emerald and Pear Necklace has now made its appearance 146 years after the death of the Maharani in 1863. The necklace was part of her personal jewelry confiscated from her in April 1849 when she made a dramatic escape to Nepal from the Fort of Chunar in Uttar Pradesh, where she was incarcerated. Her personal jewelry was however returned to her in 1860, when she came out of exile in Nepal and joined her son Duleep Singh in Calcutta, from where both mother and son set sail to England. The Maharani Jindan Kaur Emerald and Seed-Pearl Necklace, was not part of the enormous collection of jewelry taken into the custody of the British on March 29, 1849, after the annexation of the Punjab to the British Empire, that also included important and famous jewels, such as the Koh-i-Noor and the Timur Ruby. The jewelry collection of the Punjab Empire was fabled to be one of the greatest and largest treasures that fell into the hands of the British in India. The necklace was due to go on sale at a Bonhams auction in Bond Street, London, on October 8, 2009 as part of the Islamic and Indian art sale.

The length of the necklace. Is it a "Choker" or "Rope" under the Mikimoto classification of necklaces ?

According to the catalogue published by Bonhams for the auction, the Maharani Jindan Kaur emerald and pearl necklace has a diameter of 38 cm, which works out to a circumference of 119 cm or 47 ins. Thus the length of the necklace is 47 ins, which under the Mikimoto classification of pearl necklaces fall under "Rope." If what is referred to as diam. in the catalogue means the length of the necklace, then 38 cm length is equivalent to 15 ins. which falls under the category of "Choker" in the Mikimoto classification.

The size of the pearls. Are all the pearls in the necklace seed-pearls ?

The necklace is a graduated strand, with larger pearls at the center and the size of the pearls gradually decreasing towards the clasp. The necklace has been described as a seed-pearl necklace in the catalogue, which according to the modern definition of seed pearls, are pearls less than 2 mm in size or less 0.25 grains in weight. However, an examination of the photograph of the necklace provided in the catalogue, shows a distinct difference in the size of the pearls in the strand and the pearls in the emerald bead cum seed pearl pendants hanging from the necklace. The pearls in the strand are slightly bigger than the pearls in the five pendants hanging from the necklace. It is not known whether all the pearls in the necklace fall under the category less than 2mm in size, to qualify for characterization as seed pearls. Some of the pearls in the center of the strand appear to be more than 2mm in diameter !!! The total weight of the pearls in the necklace is not given.

The re-designed necklace with five pendants

Originally, the necklace had six pendants hanging from it, but subsequently one of the pendants has been removed in an attempt to re-design the necklace to give it a semblance of symmetry. The pendant that was removed is also shown in the photograph. In the re-designed necklace the largest pendant is placed at the center of the strand, and the smaller pendants are placed symmetrically, two on either side of the largest pendant. The first symmetrical pendants are placed at a distance of 10 pearls on either side of the large pendant. The second symmetrical pendants are placed at a distance of 23 pearls on either side of the large pendant. Thus the distance between the second and third pendants on either side of the large pendant is equal to 13 pearls.

Maharani Jindan Kaur Emerald and Seed Pearl Necklace with 5 Pendants

©Bonhams

Each of the pendants is made up of a polished emerald bead, mounted in gold and fringed with seed-pearl drop tassels. The total weight of the emeralds in the necklace is approximately 50 carats. The necklace is fastened at the rear with a gold clasp.

The necklace is offered for sale with a fitted cloth-covered semi-circular case

The necklace as offered for the auction, is placed in a fitted cloth-covered semi-circular case, whose interior appears to be lined with purple velvet. The velvet-lining on the lid of the case carries the following inscription in English :- "From the Collection of the Court of Lahore formed by HH The Maharajah Rungeet Singh & lastly worn by Her Highness The Late Maharanee Jeddan Kower." The case and the inscription obviously appear to be the work of Frazer and Hawes from Garrards, Regent Street, London, who sold the necklace to the present unidentified vendor, in whose family the necklace had remained for at least two generations.

Maharani Jindan Kaur Emerald and Seed Pearl Necklace inside its velvet-lined semi-circular case with inscription on the inner surface of the lid

©Bonhams

Another necklace from the Lahore Court, also retailed by Frazer and Hawes from Garrards, in a similar fitted case with inscription, appeared at a Christie's "Magnificent Mughal Jewels" sale, held in London on October 6, 1999, and has now entered the collection of Satinder and Narinder Kapany.

History of the Maharani Jindan Kaur Emerald and Seed-Pearl Necklace

When and where was the original necklace designed ?

Flourishing jewelry designing centers developed around the capital cities of new empires.

The necklace was given as a gift to Maharani Jindan Kaur between 1835 and 1839, the year of her marriage to Maharajah Ranjeet Singh and the year of the Maharajah's death respectively. Thus the necklace was obviously designed by the jewelers of the Maharajah's court in Lahore in the early 19th-century. The Punjab empire, the Maratha empires including Baroda, the Asaf Jah's Hyderabad, were some of the prosperous empires that emerged, after the declining influence of the Mughal empire following the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, and flourishing jewelry designing and crafting industries developed around these new centers of power, patronized by their royal courts.

The necklace was designed in Lahore?

In keeping with the prosperity of the Maharajah's court, a jewelry designing and manufacturing industry also developed, to supply the court with the best of jewels, designed by experienced artisans who worked for the court. Most of these artisans were descendants of designers and craftsmen who worked for the Mughal courts during their days of glory. Thus, even at Lahore, the seat of the Punjab empire, there would have been a flourishing jewelry designing and manufacturing industry, where the Maharni Jindan Kaur emerald and pearl necklace was designed and manufactured.

The necklace was designed in Bombay?

Around this time, Bombay, under the control of the British, was also a regional center for the designing and manufacturing of jewelry, and had a jewelry manufacturing industry based on pearls, that reached the pearl markets of Bombay, from the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea and the Gulf of Mannar, the traditional source of natural pearls since ancient times. Thus alternatively, the Maharani Jindan Kaur emerald and pearl necklace, could have been produced in Bombay, and later purchased by Ranjeet Singh's agents and taken to Lahore, through British territory. The necklace no doubt has distinct features of Indian design, such as the emerald and pearl pendants placed at regular intervals, the shape and polish of the emerald beads, and the use of pearl drop tassels. The nine-strand Umm Kulthum festoon pearl necklace which was also designed in Bombay, India, in the 19th-century, has some of these features.

The source of the pearls in the necklace

The source of the pearls was the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea and the Gulf of Mannar, the hub of the international pearl trade since ancient times

The source of the seed pearls in the necklace, was undoubtedly the traditional sources of pearls at that time, the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea and the Gulf of Mannar, the hub of the international pearl trade for several millennia. These pearls were produced in the species of pearl oyster that inhabited these waters, known as Pinctada radiata. Seed-pearls were usually produced in clusters inside the oyster, some of the clusters containing over a hundred seed-pearls. However, Pinctada radiata also produced single pearls of medium size reaching a diameter of about 7-8 mm. The predominant color of the pearls produced were white, but other colors such as cream, yellow, pink were also quite common. The Sri Lankan white pearls were usually of a better quality than the Persian Gulf white pearls which usually had a yellowish overtone.

Bombay became an international center of the pearl trade and industry in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Pearls produced in the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Mannar, eventually reached the Bombay pearl markets where they fetched much higher prices than the pearl markets of London. At Bombay, the pearls were graded according to size, shape, color etc. and then beaded and strung into strands for necklaces, bracelets, brooches etc. Bombay, became the regional center of the pearl industry, where a jewelry manufacturing industry based on pearls was developed. Another city where a thriving jewelry manufacturing industry based on pearls developed, since the mid-18th century, was Hyderabad, the seat of the Asaf Jah rulers of Hyderabad, where the industry thrives up to this day. Hyderabad, is the main center of the pearl jewelry manufacturing industry in India, today.

The source of the emeralds in the necklace

The source of the emeralds in the necklace, was undoubtedly Colombia, the main source of emeralds in the world at that time. Ever since emeralds were discovered in Colombia, by the Spanish conquistadors, in the mid-16th century, large quantities of these brilliant green stones reached the Mughal empire, whose seat of power was based in northern India, in Delhi and Agra. Emeralds became the favorite precious stones of the Mughal emperors, who paid better prices for the gemstone than the European monarchies. Thus, the Spanish preferred to send their emeralds to India rather than Europe, where they fetched much better prices. Emeralds were not only used in jewelry, but also in other royal paraphernalia, such as royal robes, carpets, belts, swords, thrones, sarpechs etc. Emeralds were cut and polished usually as cabochons for these purposes. Besides, emerald engraving art was also perfected during this period by the artisans of the Mughal court, and several pieces dating back to this period are found in Museums across the world, such as the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, and the Programa Royal Collections in Madrid, Spain. Cutting and polishing emeralds as beads was also a technique developed during this period, and such beads were used in necklaces, as in the case of the Maharani Jindan Kaur emerald and pearl necklace.

How did the historic necklace come into the possession of Frazer and Hawes of Garrards ?

The necklace was sold to the present anonymous owner by the crown jewelers Garrards, and it had remained in his family for at least two generations. But, how did Frazer and Hawes of Garrards come into possession of the historic necklace. It appears that after the death of the Maharani Jindan Kaur in 1863, in England, her personal jewelry was inherited by her one and only son Duleep Singh, who married twice. His first wife was Maharani Bamba Muller, by whom he had six children, three boys and three girls. After the death of his first wife in 1887, Maharajah Duleep Singh, took his second wife Ada Douglas Wetherill, by whom he had two children, both girls. The Maharani Jindan Kaur Emerald and Pearl Necklace was probably inherited by one of these eight children, who later sold it to the crown jewelers Garrards.

A short history of the Punjab

Punjab, one of the cradles of early human civilization - The Indus Valley Civilization

The name "Punjab" in the Persian language literally means "five" (panj) "waters" (aab), which obviously refers to the "Land of the Five Rivers." The five rivers that drain its territory and finally join the mighty Indus River as tributaries are, Beas, Ravi, Sutlej, Chenab, and Jhelum. The region of Punjab, situated in the Indus Valley, was one of the regions in the world where ancient human civilization originated. The Indus Valley Civilization as it is known dates back to more than 3,000 years BC, and produced large cities such as Mohenjo Daro in Sindh and Harappa in West Punjab. The Indo-Aryans settled in this region, from whom the various ancient Pungabi ethnic groups originated. The region became the cradle of ancient Hindu thoughts and beliefs, but subsequently also came under the influence of Buddhism.

Invasion of the Punjab by the Archaemenid Empire, Alexander the Great and the Mauryan Empire - 6th century BC to 1st century BC

Then followed a series of foreign invasions, and Punjab became part of the Archaemenid Empire (558-332 BC) of ancient Persia, coming under the influence of great rulers, such as Cyrus the Great and Darius. The Archaemenid Empire was overrun by Alexander the Great, who entered Afghanistan in 331 BC, and then moving downwards occupied the Punjab until 316 BC. Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Mauryan Empire then incorporated the rich provinces of the Punjab into his empire in 315 BC and Mauryan rule lasted until 180 BC. The Indo-Greek cities set up by Alexander the Great in Punjab, became the focus of a new kingdom known as the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, that was ruled by Indo-Greek Buddhist rulers such as Demetrius I and Menander I, known in India as Milinda, who set up a kingdom based in Taxila.

Invasions from Central Asia - 1st century AD to 6th century AD

Then followed a wave of invasions from Central Asia, The Indo-Scythians, the Yuezhi who created the Kushan Empire (1st century to 3rd-century AD), the Red Huns or the Kidarites in the 5th-century AD, followed by the White Huns or Hepthalites who ruled until mid-6th century AD. The region then came under the influence of the Zoroastrian Sassanid Empire of Persia, but was ruled by the Turki Shahi kingdoms, the remnants of the Kushano-Hepthalite kingdoms.

Muslim invasion from the Middle East - 8th century AD

The birth of Islam in the early 6th-century AD, and the expansion of Islam towards the east, led to the conquest and Islamization of Iran between 636 and 642. D AD. Then during the period 711-713 AD, Arab armies from the Umayyad Caliphate based in Damascus, conquered Sind and advanced into southern Punjab, occupying present-day Multan.

The rule of the Hindu Shahi dynasty, the Ghaznavids, and the Ghorids - 9th century to 12th century AD

The region came under the rule of the Hindu Shahi dynasty from the mid-9th century to early 11th century, who were then ousted by Ghaznavids, starting with the powerful Turkic ruler Mahmud, who ruled until the mid-12th century. The Ghorids from Central Afghanistan. led by Muhammad Ghori captured the Ghaznavid kingdom, occupying their former capital Ghazni and the new capital Lahore in 1186-87, and extending his kingdom past Delhi into the Ganges-Yamuna Doab.

Punjab becomes part of the Delhi Sultanate - 13th to early 16th centuries. Invasion by the Mongol Khans and Tamerlane.

After Muhammad Ghori's death in 1206, his General, Qutb-ud-din Aybak took control of Muhammad's empire, that included Afghanistan, the Punjab and Northern India, and shifted the capital from Lahore to Delhi, and after he became the Sultan, his empire was known as the Sultanate of Delhi. Qutb-ud-Din died in 1210 and his successors known as Mamluks ruled until 1290, followed by the dynasties of Khilji (1290-1320), Tughluqids (1320-1414), Sayyids (1414-1479), and the Lodhis (1479-1526). During the Delhi Sultanate, the Mongols captured Afghanistan and invaded Punjab, sacking Lahore in 1241. The Mongols also carried out two successful raids on Delhi, during the rule of Alauddin Khilji. Timur (Tamerlane) who ruled from Samarkand, also sacked Delhi in 1398-99 during the period of the Tughluq Sultans, and reduced the Sultanate to a small area surrounding Delhi. The Lodhis, who ruled between 1479 to 1526, were able to recover some of the lost territories of the Delhi Sultanate, including the Punjab.

Punjab becomes part of the Mughal Empire - Early 16th century to early 18th century

The last of the Lodhis, Ibrahim Lodhi was defeated in the Battle of Panipat in 1526, by the Mughal Emperor Babur, who founded the Mughal Empire. The Mughal Empire which originally during the period of Babur consisted of the territories in Northern India, the Punjab and Afghanistan, was gradually extended to cover the entire Indian Sub-Continent, including the Deccan and much of Southern India up to the Kavery river. The expansion of the empire took place during its classic period, starting with Akbar the Great (1556-1605), followed by Jahangir (1605-1627), Shah Jahaan (1627-1658) and ending with Emperor Aurangzeb (1658-1707). The empire reached its greatest extent during the period of Emperor Aurangzeb, and ironically it was this period that set the stage for the rapid decline of the empire after 1707. The incessant wars of expansion waged by Aurangzeb, and the wars conducted against the Marathas led by Sivaji and his successors, led to the depletion of resources and weakened the empire, setting the stage for its rapid breakup soon after Aurangzeb's death in 1707. The situation was further compounded by the war of succession that followed, and the agrarian crises that fuelled local revolts. The entry of a new player into the area, British Colonialism, attracted by the riches and the vast natural resources of the Indian sub-continent, further complicated the situation and accelerated the decline of the Mughal empire and its final demise after the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

The decline of the Mughal empire, and the Afghan intervention in Punjab

The Maratha empire expanded rapidly after the death of Aurangzeb and the region of Punjab also came under their influence until 1761. The next to break off from the Mughal empire and assert his independence was the founder of the Asaf Jah dynasty, Mir Qamar-ud-din Khan Siddiqui who founded the kingdom of Hyderabad in 1724. The invasion of Nadir Shah from neighboring Iran, in 1739, during the reign of Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah, and the sacking of Delhi and Agra, and the plundering of its wealth that included the peacock throne and other valuable jewels, including the Koh-i-Noor diamond, further weakened the Mughal empire. After Nadir Shah's death in 1747, the Commander of his Afghan bodyguard Ahmed Khan Abdali returned to his native Kandahar, in Afghanistan, and was elected Shah by a tribal council, adopting the title Durr-i-Durrani. Ahmed Shah Durrani embarked on a series of conquests, and created a vast empire at the expense of the declining Mughal empire and Nadir Shah's former empire, that extended from Meshhed to Kashmir and Delhi, including the Punjab, and from the Amu Darya to the Arabian Sea. Afghan rule in Punjab extended from the period of Ahmed Khan Abdali, through the period of his son and successor Timur Shah (1772-1793) and the period of his grandson Zaman Shah from 1793 to 1799, when Lahore was captured by Ranjeet Singh.

The power vacuum created by the decline of the Mughal empire lead to a rise in Sikh nationalism and the formation of the Sikh Confederacy

The power vacuum created by the decline of the Mughal empire in Punjab, after the death of Aurangzeb, from around 1707 to 1799 was not filled completely by other invading forces such as the Marathas or the Afghans. During this politically and militarily turbulent period, the power vacuum was filled by a political structure known as the Sikh Confederacy, made up of 12 individual Sikh kingdoms, ruled by Sikh barons. Each of these kingdoms had its own fighting army known as Misl commanded by the baron or Misaldar. The number of men in these Misls, varied from as low as 2,000 men (Nishanwalia Misl) to as high as 20,000 men (Bhangi Misl). A Misaldar Supreme Commander elected by a council of heads of each kingdom, was in overall command of all the Misls, and could bring them together in defense against a common enemy, or for any offensive action necessary. This was the first time in the long and ancient history of Punjab, the people of Punjab were having their own political institutions, and trying to shape their own destiny through them.

Maharajah Ranjeet Singh - A short biography

His birth and early years

It was during this turbulent period, when the people of Punjab were trying to take their destiny into their own hands, that Ranjeet Singh was born on November 13, 1780, at Gujranwala, the headquarters of Sukerchakia Misl, whose commander was Mahan Singh, his father. Mahan Singh controlled a territory in West Punjab, based around the headquarters Gujranwala. As a child young Ranjeet Singh suffered an attack of small pox that left him blind in one eye.

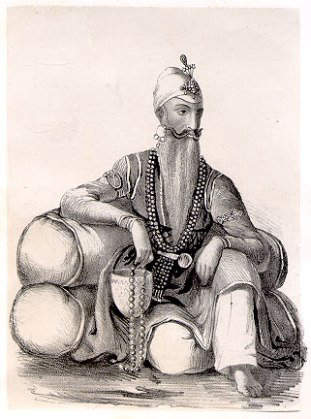

The Young Ranjeet Singh

His appointment as successor to his father at the age of 12 years, and military feat achieved soon after

Ranjeet Singh saw action at the battle front, when he was hardly 12 years old, when he accompanied his father Mahan Singh on a campaign to punish Sahib Singh Bangi, who lived in his domain and failed to pay tribute to him. Sahib Singh took refuge in the Fort of Sodhran, and Mahan Singh together with his son Ranjeet Singh laid siege to the fort, that extended for several months. During the long siege Mahan Sing fell seriously ill, and knowing very well that his end was approaching, invested his son Ranjeet Singh as his successor and chief of the Sukerchakia Misl, by applying saffron paste on his forhead. Mahan Sing then returned to Gujranwala leaving his 12-year old son as the commander of the ongoing seige. News of Mahan Singh's sickness and the investiture of his 12-year old son as chief and commander of the Sukerchakia Misl spread like wild fire all over the Punjab, and Sahib Singh's friends rushed to Sodhran to rescue him from the fort where he was entrapped. The army of Sukerchakia Misl commanded by young Ranjeet Singh, ambushed Sahib Singh's friends and routed their forces, achieving a miraculous victory that amazed and opened the eyes of all other Misaldars. The news of the sons victory reached the ailing Mahan Singh who heaved a sigh of relief just before he breathed his last in 1792.

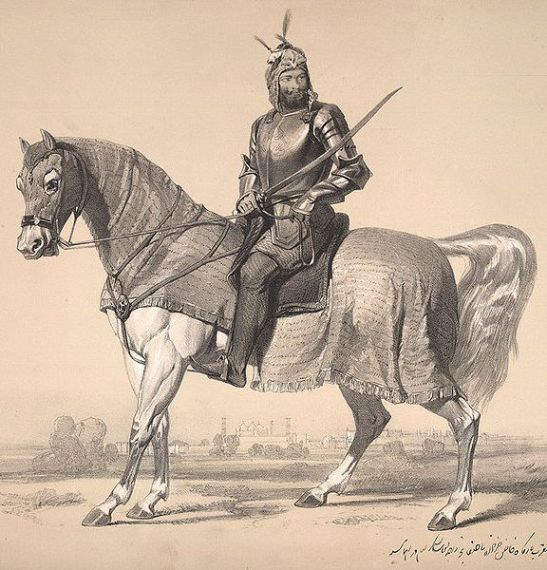

Maharajah Ranjeet Singh- the Lion of Punjab

Another miraculous feat at the age of 13 years

Entrusted with the responsibility of ruling his domain and commanding his misl, Ranjeet Singh had hardly any time for any formal education, but instead learnt the more useful arts of swimming, riding, shooting, fencing, hunting and other physical activities, that would enhance his preparedness to lead an army and take part in combat operations. It was during this period when Ranjeet Singh was out on a hunting expedition, he was attacked by one of his father's enemies Hashmat Khan, who had old scores to settle with his father. Out of fear Ranjeet Singh's horse stopped in its tracks, and Khan took the opportunity and wounded Ranjit Singh with his sword. In spite of being wounded Ranjeet Singh was able to control himself, and before Khan could make a second move, moved swiftly and with a powerful stroke of his sword cut off Khan's head. Ranjeet Singh picked up the severed head with his spear and joined his companions, who were amazed by the young 13-year old lad's feat, which they attributed to a miracle. Thus Ranjeet Singh had demonstrated his prowess as an excellent horseman and skilled fighter at a relatively young age.

Military tactics adopted by Ranjeet Singh in the face of Shah Zaman;s advancing forces. Withdrawing to the hills; re-organizing and re-training his army; attacking the Afghans village by village; Guerilla tactics used in attacking Lahore at night; pursuing withdrawing forces; and confrontation of a much reduced force inflicting crushing defeat.

1796, was also the year Shah Zaman of Afghanistan marched on the territory of Ranjit Singh, who raised an army of 5,000 horseman, and was preparing to meet the invaders at Amritsar, but later decided to withdraw to the hills as they were inadequately armed with only spears and muskets, whereas the Afghans were equipped with heavy artillery. Thus Shah Zaman was given free and unhindered access to the Punjab, while Ranjeet Singh in the hills was re-organizing his army. Later, Ranjeet Singh's army came down from the hills, and attacked the Afghans in the villagers, giving them a crushing defeat. Eventually Ranjeet Singh's forces surrounded the City of Lahore, and adopted guerilla tactics, making sorties into the city at night, and withdrawing after killing a few Afghan soldiers. However, in 1797, Zaman Shah suddenly left for Afghanistan to put down a revolt by his brother Mahmud, after leaving a contingent at Lahore, under the command of Shahanchi Khan. Ranjeet Singh pursued Shah Zaman and his forces to Jehlum, on their way to Afghanistan, harassing them and snatching goods and provisions from them. On their return journey, Ranjeet Singh and his army was attacked by Shahanchi Khan's forces, and at a battle that ensued at Ram Nagar, Ranjeet Singh dealt a crushing defeat on the Afghan forces. This was the first major victory of Ranjeet Singh, that made him the undisputed military commander of the Punjab.

Maharajah Ranjeet Singh

Zaman Shah's second attack on the Punjab, that led to his defeat, and Ranjeet Singh taking over control of Lahore City

In 1798, Shah Zaman attacked the Punjab again to avenge the defeat of 1797. The Sikh and Hindu civilians withdrew to the hills but the Muslim civilians stayed on, confident that they would not be harmed. But, Shah Zamans forces went on the rampage plundering towns and villages, including Muslim villages who lost all their livestock, stocks of food and other agricultural produce. They captured Lahore in November 1798, and were planning to attack Amritsar, when Ranjeet Singh rallied his forces and confronted Zaman Shah's forces about 8 km from Amritsar. The two armies were well matched, and Zaman Shah's forces were compelled to retreat, fleeing towards Lahore. Ranjeet Singh pursued the Afghans, and surrounded Lahore, cutting off their supply lines, burning crops and confiscating provisions that might fall into Afghan hands. Leaving some of his forces to defend Lahore, Zaman Shah proceeded towards Jhelum, on their way back to Afghanistan, pursued by Ranjeet Singh's forces.

The remaining Afghans in Lahore, tried hard to dislodge the Sikhs, to break the cordon and lift the siege, but all their efforts were in vain. Ranjeet Singh was now the undisputed leader of the Punjab, and the people of Lahore, Sikhs, Hindus as well as Muslims made a joint appeal to Ranjeet Singh to free them from the tyrannical rule of the Afghans and some of the Sikh collaborators, the Bhangi sardars. In response to this appeal Ranjit Singh mobilized an army of 25,000 men that included Sikhs, Hindus as well as Muslims, and marched towards Lahore on July 6, 1799. In the morning of July 7, 1799, Ranjeet Singh breached the walls of the city, and in the panic and confusion that was created, Muslims inside the city opened the gates for Ranjeet Singh's forces, who entered the city and occupied a large part of it without any resistance. The Afghan forces and their Sikh allies either surrendered or were killed. Immediately after taking possession of the city, Ranjeet Singh paid an visit to the Badshahi Mosque, to pay his respects, a gesture that won the hearts of the Muslims of the City.

Ranjeet Singh is crowned the Maharajah of the Punjab on April 12, 1801

Ranjeet Singh who was now 21 years old and the undisputed leader of the Punjab, was crowned as the Maharajah of the Punjab on April 12, 1801, the coronation being conducted by Sahib Singh Bedi, a descendant of Guru Nanak Dev, the founder of the Sikh religion. Ranjit Singh made Lahore the capital of his kingdom. In 1802, he took control of the holy city of Amritsar. The following years he spent fighting the Afghans and driving them out of the Punjab. He then embarked on a campaign of conquest, capturing Pashtun territory that included Peshawar, the province of Multan in southern Punjab, Jammu and Kashmir, and the hill states north of Anandpur Sahib, the largest of which was Kangra. He extended his territories upto Ladakh and China. Thus, his vast empire stretched from the Indian Ocean to the Himalayas.

Maharajah Ranjeet Singh was a devout Sikh, but opted for a secular form of government where equal opportunities were provided for all irrespective of religion

Ranjeet Singh was a devout Sikh, who loved and admired the teachings of the 10th Guru of Sikhism, Guru Gobind Singh. He built two of the most sacred temples of Sikhism, the Takht Sri Patna Sahib, at the birth place of Guru Gobind Singh and Takht Sri Hazur Sahib, the final resting place of Guru Gobind Singh in Nanded, Maharashtra. He was also a generous patron of the Harmandir Sahib, the Golden Temple, the most sacred shrine of the Sikh religion, and much of the intricate gold and marble work in the temple was conducted under his patronage. However, in spite of being a devout Sikh, he never attempted to force Sikhism on any of his subjects. He adopted a secular form of government, and none of his subjects were discriminated against on account of their religion. The majority of his subjects were Muslims, yet they were intensely loyal to their Sikh ruler, who respected their religion, customs and traditions. He appointed learned people of all religions as his courtiers and advisors. His finance minister was the Brahmin Dina Nath and his foreign minister a Muslim, Fakir Azizuddin. Under his rule people were recognized and promoted on their ability and not their religion. The Maharajah in turn was held in high esteem by his people, and the courtiers and advisors who worked for him. The esteem in which the Maharajah was held by his subjects was clearly highlighted by the following episode. When Fakir Azizuddin, the foreign minister of the Sikh empire, met the British Governor-General of India, George Eden, the 1st Earl of Auckland, at Simla, the Governor-General inquired from the foreign minister, as to which of Maharajah's eyes was missing. Fakir Azizuddin then replied, "The Maharajah is like the sun and the sun has only one eye. The splendor and luminosity of his single eye is so much that I have never dared to look at his other eye." The Governor-General was said to have been very much pleased with this reply that he gave his gold watch to Azizuddin.

Harmandir Sahib-The Golden Temple at Amritsar

Maharajah Ranjeet Singh, the first Asian ruler to modernize his army to European standards

Maharajah Ranjeet Singh, who came to be known as the "Lion of the Punjab" has gone down in history as the first Asian ruler to modernize his army to European standards, well ahead of the Japanese re-structuring of the 1880s. Early in his military career, Ranjeet Singh had seen how well trained and disciplined British troops had vanquished Indian forces vastly superior in numbers. The gifted military genius that he was, he realized the crucial role played by the infantry and the artillery in any modern warfare. Ranjit Singh first engaged some deserters from the army of the East India Company in 1802, to train his own platoons of infantry. He also sent some of his own men to Ludhiana to study the British methods of training and tactics. Initially, the Sikhs themselves were reluctant to join the infantry, and Ranjith Singh was forced to recruit Punjabi Muslims, Afghans and Gurkhas to the infantry, who were trained by the deserters of the British army. The newly trained troops were soon tested in a short campaign during the winter of 1803-04, against Ahmad Khan Sial of Jharig and the Zamindars of Uchch, and they came out with flying colors. The success of the infantry, and the fact that the Maharajah himself regularly attended their training sessions, soon elevated the infantry to an enviable service, which the Sikhs too began to join in large numbers.

Ranjith Singh, then diverted his attention to strengthening his artillery. His artillery was hitherto limited to swivel guns mounted on camels or other animals. He increased the number of guns, and undertook the casting of guns of larger caliber, as well as the large scale manufacture of ammunition. He then inducted the services of European officers into the Sikh army, veterans of the Napoleonic wars. The first Europeans to be recruited were Jean Baptiste Ventura and Jean Francois Allard in 1822, who were charged with the raising of a special corps of the regular army. While General Ventura trained battalions of infantry, General Allard trained the cavalry. In 1827, another French officer, General Claude Auguste arrived in Lahore, and was placed in charge of the training and command of the artillery regiment. The American colonel Alexander Gardner who arrived in 1832 was also placed in joint command of the artillery.

The policy adopted by Maharajah Ranjeet Singh vis-a-vis his southern British neighbors

After the re-organization of the army, the infantry became the central force of the army, with the cavalry and artillery serving as supporting arms. Maharajah Ranjeet Singh eventually developed a formidable military machine that helped him to carve out and maintain a extensive kingdom for almost 40 years of his rule, amid hostile and ambitious neighbors, including the British. The military genius and astute politician that he was, Maharajah Ranjeet Singh, was fully aware of the British military prowess and their expansionist intentions. Thus he shrewdly avoided any attempt to invade states south of the Sutlej river which was under British rule, for fear of provoking the British. He opened a political dialogue with his southern British neighbors, and continued to maintain friendly relations with them throughout his rule. The British too were well aware of the strength of his newly re-organized army in accordance with modern European standards, and refrained from making any rash moves that would lead to an all out confrontation. The British adopted a patient wait-and-see attitude, knowing fully well that after Maharajah Ranjeet Singh was gone, a struggle for succession would lead to instability, preparing the fertile ground for their intervention.

The Maharajah's harem

It is said that Prince Duleep Singh once remarked, "I am the son of one of my father's forty six wives." The Prince was obviously referring to the Maharajah's harem. The Maharajah had been susceptible to the charms of the fair sex, through out his life, since the days he attained adulthood. However, in spite of his marriage and commitment to a large number of women, his household was free of any intrigue as long as he lived. He never allowed his married life to interfere with his duties as a ruler. He always kept his heart and head scrupulously apart. He also made sure that his wives, as Queens of the kingdom, involved themselves wholeheartedly in the welfare of the people, such as undertaking relief work at the time of floods, famine or epidemic, and popularizing handicrafts like phulkari knitting and fine arts among the people.

There were four categories of women in the Maharajah's harem. The first category of wives consisted of nine queens, whom he had married according to Sikh customs and traditions. The second category of wives also consisted of nine queens, whom he had adopted as wives by a common practice that exists in Punjab even today, known as "Chadar Andazi" by which a widowed woman was re-married, providing a mantle of protection for her. The third category consisted of seven women who were courtesans. The fourth category of women were the concubines, whose number must have been 21, if Duleep Singh's estimate of 46 wives is correct.

Some of his regular wives who bore him children eligible for succession

Among the more important of his regular wives married according to Sikh customs, were Mehtab Kaur of the Kanhia Misl, the daughter of Rani Sada Kaur, whom he married, when he was 16 years old, in the year 1796. Rani Mehtab Kaur gave birth to three sons; the eldest Ishar Singh died young at 1½years of age. The second and third sons were twins, Sher Singh and Tara Singh. Sher Singh was the strongest claimant to the throne after Maharajah Ranjeet Singh, being the eldest surviving son of the senior most wife of the king. His second wife was Raj Kaur of Nakai Misl, the daughter of Khazan Singh Nakai, whom he married in 1798, at the age of 18 years. Rani Raj Kaur gave birth to a son Kharak Singh in 1801 who became the heir-apparent to Maharajah Ranjeet Singh, being the Maharajah's eldest son. Two of his other favorite wives were the two Rajput princesses, sisters from the same family, from the hill country, Kangra, Guddan and Rani Raj Banso, the daughters of Raja Sansar Chand. They were the most charming women in the Maharajah's harem. Another favorite of his regular wives was Rani Jindan Kaur, daughter of Sardar Manna Singh Aulak, the Royal Kennel Keeper at the Court of Lahore, the ninth and the last regular wife he married, according to Sikh customs in 1835, and who bore him his last son Duleep Singh in 1838, just 10 months before his death in 1839.

The Young Maharani Jindan Kaur

Maharajah Ranjeet Singh's court renowned for its fabulous riches

Some first-hand accounts of the riches of Maharajah Ranjeet Singh's court

Ranjeet Singh's court was famous for its patronage of the arts and sciences, and for its riches. Some of the first hand accounts of the riches of his court came from western writers. Alexis Solykoff, the Russian painter, who visited his court, wrote : "What a sight! I could barely believe my eyes. Everything glittered, with precious stones and the brightest colors arranged in harmonious combinations. Upon the Maharajah's death, his body was carried through the streets to his funeral pyre in a golden ship, with sails of gilt cloth to waft him into paradise." The Maharajah, assembled a priceless collection of jewels, that included the world's most precious jewel, the "Koh-i-Noor," and other famous jewels such as the "Timur Ruby." The British astonishment over the Maharajah's fabulous collection, was clearly expressed by the nephew of Henry Edward Fane, a personal aide of Colonel Wade, the British political agent posted in Ludhiana : "The dresses and jewels of the Raja's court were the most superb that can be conceived; the whole scene can only be compared to a gala night at the Opera. The minister's son, in particular the reigning favorite of the day (Hira Singh) was literally one mass of jewels, his neck, arms and legs were covered with necklaces, armlets and bangles, forms of pearls, diamonds and rubies, one above the other, so thick that it was difficult to discover anything beneath them."

Maharajah Ranjeet Singh an unassuming and unpretentious character used to simple modes of dressing

In receiving foreign visitors, instead of using his permanent palace in Lahore, he would sometimes set up scarlet tented pavilions, on gold and silver poles near the river, which served as a backdrop to the elaborate setting. The tents were lined with luxurious shawls from Kashmir, and the floor was covered with fine carpets. Men and women who were in attendance at the temporary palace, glittered due to the jewel-studded robes they wore. The whole interior of the tent glittered, but the person of the Maharajah presented a picture that was in stark contrast to the shining and shimmering surroundings. Maharajah Ranjeet Singh, the Lion of Punjab, the unchallenged emperor of the first Sikh and Punjabi empire, was seated inside the tent, not on the golden throne meant for him, but on a simple chair or sometimes on the carpet, dressed in plain clothes, an unassuming and unpretentious diminutive figure, yet a compelling personality, full of energy and boundless curiosity. In spite of his simple mode of dressing, Maharajah Ranjeet Singh was renowned as the owner of one of the most fabulous collection of jewels, some of which were once owned by the powerful Mughal emperors, which included the 186-carat "Koh-i-Noor diamond," one of the oldest and most famous diamonds in the world, with a history dating back to at least 3,000 years B.C. and the 361-carat "Timur Ruby" that was once owned by Tamerlane, the greatest conqueror of the 14th-century, from Samarqand, Uzbekistan. His collection also included Mughal jade and crystal. He mobilized artists and craftsmen to work for his court, without regard for religious differences. His simple golden throne was designed and manufactured by a renowned Muslim craftsman, and craftsmen of all religions worked on the decorative gilding and marble work of the "Harmandir Sahib," the Golden Temple, the holiest of all Sikh shrines.

The Throne of Maharajah Ranjeet Singh-Designed by Hafiz Muhammad Multani

The death of Maharajah Ranjeet Singh and the succession struggle that followed

Ranjit Singh was cremated in Lahore near the Badshahi Mosque. Four wives and seven concubines committed Sati on his funeral pyre

Maharajah Ranjeet Singh died on June 27, 1839, following a severe stroke, after a reign of nearly 40 years, that saw the unification of the Punjab as well as the various Sikh factions into a single viable state, with Lahore as its capital, and created an empire that went beyond the borders of the Punjab, extending from the Indian Ocean to the Himalayas. His final rites were performed in Lahore, both by Sikh as well as Hindu priests. One of his regular wives Maharani Mahtab Devi Sahiba (Guddan Raj Banso), the Rajput Princess of Kangra, and daughter of Maharajah Sansar Chand, was determined to commit Sati in keeping with Hindu Rajput traditions, and no amount of persuasion could prevent her from carrying out her desires. She committed Sati, as the Maharajah's head lay in her lap. Some of the other wives also joined her and committed Sati. In all four wives and seven concubines were reported to have committed Sati, by throwing themselves on his funeral pyre. Today, the ashes of these eleven wives are placed in tiny urns, surrounding the large marble urn, in the shape of a lotus, containing Maharajah Ranjeet Singh's ashes, in the center of the tomb, the Samadhi of Ranjeet Singh, at Lahore. His youngest wife, who was also his 9th regular wife, Maharani Jindan Kaur did not commit Sati, perhaps because she had a 10-month old baby to feed and look after.

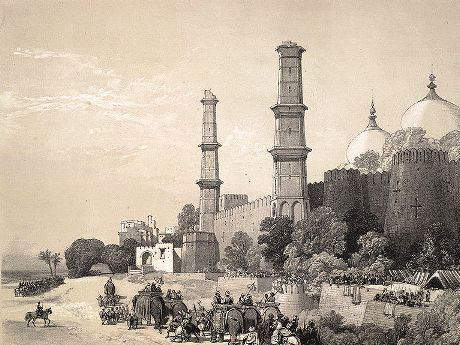

Samadhi of Maharajah Ranjeet Singh at Lahore

The struggle for succession after Maharajah Ranjeet Singh's death

Maharajah Ranjeet Singh was succeeded by his eldest son Kharak Singh from his second wife, Raj Kaur, instead of his eldest surviving son Sher Singh by his most senior wife, Mehtab Kaur, daughter of Rani Sada Kaur. The succession caused a lot of bitterness among Ranjit Singh's heirs. Kharak Singh was not fit and prepared to rule his father's vast empire, and was unable to control the various factions within his kingdom. Therefore, Kharak Singh's eldest son Nau Nihal Singh, who was just 18 years old took control of the kingdom himself from his father, on October 8, 1839. Kharak Singh died of poisoning on November 5, 1840, and Nau Nihal Singh was to formally take over as king after his father's death. However, unfortunately when Nau Nihal Singh was returning from his father's funeral, he was fatally injured by debris from a collapsing building that smashed his head. It is not known whether the building collapse was accidental or deliberate. Nau Nihal Singh, was succeeded by Sher Singh, the eldest surviving son of Ranjeet Singh by his most senior wife Rani Mehtab Kaur, who was believed by many to be the actual claimant to the throne of the Punjab, after Ranjeet Singh's death. Sher Singh's succession did not come automatically. He won the throne only after a protracted siege of the Lahore fort, that was held by the Royal family. He was installed as king, in January 1841, but was himself killed just two years after taking office, in Septmber 1843, together with Dhian Singh, in a plot hatched by the Sandhawalias, cousins of Sher Singh, who also had designs on the kingdom. Raja Dian Singh's son Raja Hira Singh, with the support of the army, wiped out the Sandhawalia faction, and captured the fort of Lahore. Then on September 16, 1943, the army proclaimed Ranjeet Singh's youngest son, Duleep Singh who was just five years old, as king, with his mother Jindan Kaur as regent and Hira Singh was appointed as Wazir. The army overlooked the claim of another son of Ranjeet Singh, Prince Pashaura Singh, to the throne of Punjab.

Maharani Jindan Kaur takes full control of the government, with the blessings of the army, acting as regent to Maharajah Duleep Singh

Maharani Jindan Kaur's inner potential as an able administrator is brought to the fore after she assumes full control

The army generals treated Jindan Kaur, rwith great respect, addressing her as Mai Sahib or Mother of the Khalsa Commonwealth. Jindan Kaur made use of this respect for her by the army, to advance the cause of her son Duleep Singh and to protect him from his enemies. She succeeded in eliminating the dominance of the Hindu Dogras, and replacing Hira Singh with her brother Jawahar Singh as Wazir. She now assumed full control of the government, with the blessings of the army, ruling the Punjab in the name of her son. Rani Jindan Kaur had all the personal characteristics needed to make a successful sovereign, such as great beauty, personal charm and strength of character. Above all she had the allegiance of her army, a vital factor that would ensure her survival in the post Ranjeet Singh era of political instability. She held court and transacted state business in public. She reviewed the troops and addressed them. She was confronted with a host of problems after she assumed office, such as the troops clamoring for an increase in pay, feudatory chiefs demanding for a reduction of enhanced taxes and burdens imposed upon them by Hira Singh, problems caused by Prince Pashaura Singh and Ghulab Singh, and the revenues of the state not sufficient to meet the increase in cost of civil and military administration. On top of this a panic was created that a British force was heading towards Lahore, accompanied by Peshaura Singh and assisted by Ghulab Singh.

Maharani Jindan Kaur- Mother and Regent to Duleep Singh

Maharani Jidan Kaur directed her energies to heal the rift between the Sikh Sandhawalia and the Hindu Dogra factions, something which the British hated

Maharani Jindan Kaur, demonstrated her strength of character, in tackling these problems, and obtained the assistance of a newly appointed council of elder statesman and military generals. The council first directed its attention towards the rebels Prince Pashaura Singh and Ghulab Singh, whose activities could make things uncomfortable for the government. Prince Pashaura Singh was summoned to Lahore and persuade to return to his Jagir in early 1845. A 35,000-strong army moved into Jammu to contain Gulab Singh, the Dogra chief's activities, who was accused of being a traitor for secretly negotiating with the British against the Sikh kingdom, and charged with treachery and intrigue, against the sovereign. The army returned to Lahore, with Gulab Singh as hostage, in April 1845. She gave a pay increase to the soldiers, and installed her brother Jawahar Singh, formally as the Wazir (prime minister). She even started negotiations with Gulab Singh, with a view of healing the rift between the Sikh Sandhawalias and the Hindu Dogras, something which the British hated, as it went against their policy of fishing in troubled waters.

Maharani Jindan Kaur

The murder of Jawahar Singh by the Sikh Khalsa and two crucial appointments made soon after by the Khalsa that spelt the doom of the Sikh empire

However, more intrigues were to follow soon. Prince Pashaura Singh was instigated by the Dogra brothers, to rebel and take over Attock, which he did, but soon Prime Minister Jawahar Singh, rushed forces to Attock, to suppress the rebellion, and in the process Pashaura Singh was killed. The Sikh Khalsa army, suspected the involvement of Jawahar Singh in the murder, and killed Jawahar Singh, right in front of Maharani Jindan Kaur and her son Maharajah Duleep Singh, on September 21, 1845. The death of her own brother right in front of her eyes, was something too much for the Maharani to bear, who gave vent to her anguish with loud lamentation. Maharani Jindan Kaur publicly vowed revenge against her brothers killers, but still remained regent to the young Maharajah and was committed to the cause of the Sikh kingdom. Later in November 1845, she appointed Lal Singh as Wazir and Tej Singh as commander of the army, with the approval of the Khalsa council. The appointment of these two men spelt the doom of the Sikh empire. The two men were actually recent converts to Sikhism, but were originally high caste Hindus, and appear to have been sympathetic to the Hindu Dogra faction, and maintained contacts with the British before and during the war. Their subsequent conduct during the first Anglo-Sikh war caused the defeat of the well-trained Sikh army, and the collapse of the Sikh empire.

The First Anglo-Sikh War

The motivation for British designs on the Punjab

Soon after the death of Maharajah Ranjeet Singh, and during the succession struggles that followed, the British East India Company became active and increased its military strength, moving 32,000 troops to the Sutleg frontier, under the pretext of securing its northernmost possessions. The British who had attacked and annexed the Sindh, in the previous year, had set up a military cantonment at Ferozepur, just a few miles from the Sutleg river. The British designs on the Punjab was motivated by the following reasons :- 1) The Punjab was the wealthiest kingdom in the region holding enormous treasures in the form of jewels and jewelry. 2) It was the last remaining independent kingdom in India not under their direct influence. 3) The Punjab was the only remaining formidable force in the region, with a well-trained army, that could be a potential threat to the British hold on India.

Events that led to the declaration of war by the British

The military build-up at the borders continued, causing increased tension within the Punjab and the Khalsa. In the midst of accusations and counter accusations, diplomatic relations between the Sikh Darbar and the British East India Company was broken off. The British began moving another division of its army, the elite Bengal army under the command of Sir Hugh Gough towards Ferozepur. In response the Sikh army with the confidence gained after decades of thorough training by competent military experts from Europe and America and motivated by the Mai Sahib Jindan Kaur, decided to go on the offensive, in keeping with her motto, "throw the snake into your enemy's bosom." The snake she was referring to was the powerful Sikh army. The Sikh army crossed the Sutleg on December 11, 1845, ostensibly to occupy a former Sikh possession, the village of Moran, named after one of Maharajah Ranjeet Singh's favorite Muslim courtesans, on the east side of the river. The British considered this as a hostile move and declared war.

The first phase of the war, in which the Sikh soldiers fought valiantly, but their commanders appeared to be safeguarding the interests of the enemy

The Sikh army entered the war with enthusiasm and fought bravely. A division of the Sikh army under the commander Tej Singh advanced towards Ferozepur, and could have easily attacked or surrounded the exposed British division there, but failed to do so, to the bewilderment of the soldiers, who became suspicious of Tej Singh's command. Another Sikh army division under Lal Singh clashed with Gough's advancing Bengal army, on December 18, 1845. The next battle was an attack on the large Sikh entrenchment at Feroze Shah on December 21, 1845, but the Sikh artillery caused heavy casualties among the British. The Sikh units fought back fiercely and were able to drive back most of the English units in total disarray. The British commanders were expecting a total defeat the next day, in the face of the fierce Sikh onslaught. However, the next morning the British and Bengali units, rallied and fought back, and drove the Sikhs from their fortifications. What puzzled many was that Lal Singh did not make any effort to rally or reorganize his army for a counter attack. At this point, Tej Singh's army appeared, and Gough's exhausted army faced certain defeat and disaster, had his army attacked. But surprisingly Tej Singh's army withdrew instead of taking on the enemy.

The second phase of the war in which the Sikh soldiers continued to fight fiercely and stubbornly, but unfortunately a section of the army was trapped and massacred by the British troops.

The Sikh army was dismayed and demoralized by the inexplicable behavior of their commanders, and when news reached Lahore about the army's failure, Maharani Jindan Kaur, picked 500 dedicated officers and exhorted them to make renewed efforts on behalf of the Sikh nation. She sent fresh units and commanders into the battle. When the war resumed, the Sikhs tried to cut off Gough's supply and communication lines, that resulted in a battle near Aliwal on January 28, 1846, which they lost. The final battle came when Gough's army attacked the main Sikh bridgehead at Sobraon on February 10. Tej Singh the commander had already suspiciously deserted the army early in battle, but the army continued to fight fiercely and stubbornly as at Ferozeshah. however, Gough's troops eventually made incursions into their positions. The bridges behind the Sikh positions collapsed due to British artillery fire or were deliberately destroyed by Tej Singh ostensibly to prevent British pursuit as he escaped. The Sikh army was trapped, unable to cross the river, and none of them surrendered. The British troops showed little mercy and the result was a massacre of thousands of Sikh soldiers. The war ended in a defeat for the Sikh Khalsa, and set the stage for the total disintegration of the empire created by the hard work, sacrifice and dedication of a single individual - Maharajah Ranjeet Singh.

An attempt by modern historians to explain Lal Singh's and Tej Singh's behavior during the first Anglo-Sikh war.

Present day historians have expressed the view that Lal Singh and Tej Sing, the prime minister and the commander of the army were actually British spies on the pay roll of the British East India Company, corresponding with British officers, and betraying state and military secrets throughout the war. Lal Singh's and Tej Singh's behavior during the course of the war, refusing to attack when opportunities were available, and deserting their armies during crucial battles consolidate this viewpoint.

Raja Lal Singh- Prime Minister and one of the commanders of the first Anglo- Sikh war

Conditions of the peace treaty that followed the first Anglo-Sikh war of 1845/46

Some of the conditions of the peace treaty that was signed in Lahore between the Lahore Darbar and the British East India Company, on March 9, 1846, soon after the war ended, are as follows :-

1) The Jullundur Doab between the Beas River and the Sutlej River to be surrendered to the British.

2) The Lahore Darbar to pay an indemnity of 15 million (1.5 crore) rupees.

3) Maharajah Ranjeet Singh to continue as ruler of Punjab, with his mother Maharani Jindan Kaur remaining as regent.

4) The Sikh army was greatly reduced in size from its original 80,000 to around 20,000 thousand troops, that set the stage for the second Anglo-Sikh war.

5) The British troops were to be withdrawn from Lahore by the end of the year 1846.

As the Lahore Darbar could not raise the money immediately to pay the indemnity, the Darbar agreed to surrender additional lands to the British East India Company in lieu of payment. Accordingly, Kashmir, Hazarah and the territory between the Beas and the Indus was surrendered to the British. However, subsequently Ghulab Singh the Raja of Jammu came to an arrangement with the East India Company, signing the treaty of Amritsar, by which he purchased Kashmir from the company for 7.5 million rupees, and was granted the title of Maharajah of Jammu and Kashmir, but still recognizing British Sovereignty.

Maharajah Duleep Singh entering his palace at Lahore escorted by British troops.

The Treaty of Bhyroval by which Maharani Jindan Kaur was replaced by a British resident and a regency council

The Treaty of Bhyroval was intended by the British to tighten their grip on the Punjab, and to avoid withdrawing their troops from Lahore as agreed by the first treaty. According to this treaty signed on December 16, 1846, Maharani Jindan Kaur was removed as regent to her son Maharajah Duleep Singh, and replaced by a British Resident in Lahore Sir Henry Lawrence, supported by a Regency Council, ironically headed by Tej Sing, the former commander of the Sikh army, who treacherously facilitated the British victory in the first Anglo-Sikh war. The appointment of Tej Singh caused a lot of anger and resentment among the Sikh population, and increased the sympathy towards Maharani Jindan Kaur. The Maharani was given an annual pension of Rs. 150,000. British troops continued to be stationed in Lahore in support of the resident political agent and the regency council. The Sikh Darbar ceased to exist as a sovereign political body, and the East India Company took effective control of the government.

The shameful and humiliating treatment of Maharani Jindan Kaur after her forceful retirement

The Maharani was confined to her palace and restrictions placed on the number of visitors she could receive

Maharani Jindan Kaur retired gracefully to a life of religious devotion in the palace, but continued to be treated with unnecessary acrimony and suspicion, because of the respect she commanded from the general Sikh population and the possibility that she could influence future political events in her former domain. The British continued to see her as a major threat to their control of the Punjab, given her previous record of organizing Sikh resistance, and rallying her armies to battle. The British Resident Sir Henry Lawrence and the Governor General Viscount Hardinge, both accused her of fomenting intrigue and influencing the politics of the Punjab. They placed restrictions on the number of visitors she can receive in a month, and also interfered with her personal freedoms, such as instructing her to remain in purdah, like the ladies of the royal families of Nepal, Jodhpur and Jaipur.

The British resident was waiting for a pretext to separate the mother and the son

What was particularly worrying for the British was the influence she could exert on her son the young Maharajah, and they were waiting for the slightest pretext to separate the mother and the son. The pretext was created, when in August 1847, the young Maharajah refused to confer the title at the time of Tej Singh's investiture as Raja of Sialkot in August 1847, alleged to be at the instigation of his mother. The British tried to implicate her further in a conspiracy known as the Premilla Plot, in which Sir Henry Lawrence and Tej Singh were to be murdered at a fete at the Shalimar Gardens. An inquiry held into both incidents cleared her of any involvement, yet on the orders of Henry Lawrence, the mother and son were separated, and Maharani Jindan Kaur was sent to the Summan Tower of Lahore Fort, from where she was transferred to the fort at Sheikhurpura, for incarceration in September 1847. Her annual allowance was drastically reduced from Rs 150,000 to a mere Rs. 48,000.

Maharani Jindan Kaur is expelled from the Punjab fearing her presence would exacerbate the rebellion in Multan

In 1848, Lord Hardinge's term of office as Governor General expired, and he went back to England, with Sir Henry Lawrence who took leave of absence. Viscount Hardinge was replaced by the Earl of Dlahousie as Governor-General, and Henry Lawrence by Frederick Currie as British resident in Lahore. Soon after their arrival, the Multan rebellion broke out in April 1848, and their attitude towards Maharani Jindan Kaur hardened. Dalhousie ordered Currie to expel Maharani Jindan Kaur from Punjab perhaps fearing that her presence in Punjab would exacerbate the rebellion brewing in Multan. Accordingly, she was moved to a prison in Firozpur, and later Benares, still in the British dominions. The humiliating treatment of the Maharani caused deep resentment among the people of the Punjab and even provoked a response from the ruler of neighboring Afghanistan, Amir Mohammed Dost, who protested to the British about her treatment. While at Benares allegations were made by Major MacGregor, who was in charge of her incarceration, that she was in correspondence with the rebel leaders Diwan Mul Raj and Sher Singh at Multan. Some of the letters written by her were intercepted and an alarm was created when one of her female attendants escaped from Benares.

Lord Dalhousie-Governor-General of India

Maharani Jindan Kaur is incarcerated in the Fort of Chunar from where she makes a dramatic escape to Nepal, leaving a note for the British, who confiscate all her gold and jewelry

She was then moved to the Fort of Chunar in Uttar Pradesh, from where she escaped to Nepal disguised as a maid-servant, on April 19, 1849, leaving a note for the British : "You put me in the cage and locked me up. For all your locks and your sentries, I got out by magic......I had told you plainly not to push me too hard - but don't think I ran away, understand well, that I escape by myself unaided.....When I quit the Fort of Chunar I threw down two papers on my Gaddi and one I threw on the European Charpoy, now don't imagine, I got out like a thief!" She fled to the Himalayas disguised as a beggar woman, and moved to Kathmandu, in Nepal, where she was given political asylum by the Prime Minister Jung Bahadur, mainly as a mark of respect to the memory of the late Maharajah Ranjeet Singh. The Nepalese government not only gave her a residence at Thapathall, but also an allowance for her maintenance. The British authorities confiscated all her gold and jewelry, said to be worth around Rs 900,000 - which also included the emerald and seed-pearl necklace, the subject of this webpage - that had been left in the government treasury at Benares, and rescinded her pension.

Maharani Jindan Kaur's period of exile in Kathmandu, Nepal

Maharani Jindan Kaur's exile in Kathmandu, Nepal, lasted for over ten years, until 1860. Her initial period of stay in Nepal was quite happy, and she spent her time studying the Sikh and Hindu scriptures, and doing charitable work through a temple she had built near her house. However, even in exile the British seemed to be scarred of the ex-Maharani, believing that she was capable of engaging in political intrigue to secure the revival of the Sikh dynasty in neighboring Punjab. Thus the British residency in Kathmandu kept a vigilant eye on her activities in Nepal, exerting constant pressure on the Nepalese government to restrict her movements. The Maharani was portrayed as a dangerous troublemaker who could create disaffection against the British and whip up tensions in neighboring Punjab. Thus the Nepalese government turned hostile towards her and were compelled to impose humiliating restrictions on her. She protested against the indignities and restrictions imposed upon her by Jhung Bahadur, that led to several confrontations between her and the Nepalese government. The British apparently not satisfied with making her life miserable in Nepal, went on a campaign of tarnishing her name in the British Press, by referring to her as the "Messalina of the Punjab" comparing her to Messalina, the wife of the Roman Emperor, Claudius, who was a licentious seductress, powerful and influential, and too rebellious to control.

Second Anglo-Sikh War

Causes of the second Anglo-Sikh war

The possible causes of the second Anglo-Sikh war of 1848/49 just two years after the first Anglo-Sikh war of 1845/46, that was decided in favor of the British with heavy loss of life on the side of the Sikhs, that resulted in the British becoming the de facto rulers of the Punjab State, can be summarized as follows :-

1) To fulfill the imperialist ambitions of the British, to subjugate the Sikh kingdom and annex the Punjab to the British Empire, carrying forward the British flag to the natural boundary of India on the northwest, and thus bringing the entire Indian sub-continent under their rule.

2) In the first Anglo-Sikh war victory was denied to the Sikhs, clearly due to the treachery of its commanders and not due to any weakness on the part of the Sikh army, and there were many ex-soldiers among the Sikhs, who were anxiously waiting for an opportunity to avenge the defeat of 1845/46.

3) The signing of the treaty of Bhyroval on December 16, 1846, under which the key provision of the first peace treaty signed on March 9, 1846 that required the withdrawal of British troops by the end of the year 1846, was changed, enabling an indefinite presence of British troops on Punjab soil, angered the people of Punjab.

4) The removal of Maharani Jindan Kaur as the regent for her son Maharajah Duleep Singh, and the replacement by a Regency Council, headed by the treacherous Tej Singh, who was responsible for the Sikh defeat in the first Anglo-Sikh war.

5) The maltreatment and humiliation of Mai Sahib, the Mother of the Sikh Nation, Maharani Jindan Kaur, after her removal as regent, caused a lot of anger and resentment among the Sikhs of Punjab.

6) Stripping of all powers of the Sikh Darbar that ceased to exist as a sovereign political body and a concomitant increase in the powers of the British resident, with full authority to direct and control all matters in every department of the State.

7) The desire of the Punjab nation to preserve its hard won independent identity, created by Maharajah Ranjeet Singh, after centuries of foreign subjugation beginning with Archaemenid invasion of 558-332 BC and ending with the formation of the Sikh Confederacy following the decline of the Mughal empire after the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, and the eventual emergence of Maharajah Ranjeet Singh as the undisputed leader of the Sikhs, uniting all Sikh and Punjabi factions under a single Punjabi nation.

The Multan Rebellion that became the rallying point for all anti-British Sikh forces

The second Anglo-Sikh war began as a localized rebellion on April 18, 1848, in the Muslim dominated Multan in southern Punjab, sparked by the killing of two British officers who accompanied the new governor, General Khan Singh Man to Multan, to take over duties from the former governor Diwan Mul Raj, who had resigned previously unable to pay the arrears of revenue and increased levy imposed, by the British Resident of Lahore, Frederick Currie. Mul Raj's soldiers took the law into their own hands and killed the British officers, beginning the rebellion. Soldiers who escorted the new governor and the British officers from Lahore, defected and joined Mulraj's rebel army. As news of the rebellion spread, large numbers of Sikh soldiers deserted the regiments loyal to the Lahore Durbar, and joined the rebels under the leadership of Mulraj. The news of the rebellion reached Lahore on April 21, 1848, and Currie sought for assistance from Governor-General Dalhousie and Hugh Gough, the commander of the Bengal army, to suppress the rebellion at Multan. However, Gough and Dalhousie decided not to send any assistance until the end of the hot weather and the monsoon seasons, which would be in November. Currie took immediate action to expel Maharani Jindan Kaur from Punjab, on the orders of Dalhousie, fearing that she could become the focus of the new uprising.

The British begin a siege of Multan in August 1848, but the siege is not effective due to lack of troops

In the absence of any British troops to quell the rebellion, Herbert Edwardes, the British Political Agent in Bannu, mobilized some loyal Sikh regiments, which included one commanded by Sher Singh Attariwala, the son of Chattar Singh, and some Pashtun irregular troops, and marched towards Multan. They met Mulraj's army near the Chenab river on June 18, 1848, and after a fierce battle drove them back to the city, but was not able to attack the fortified city. Currie then ordered a small contingent of the Bengal army, under General Whish, to march towards Multan, to begin a siege of the City. After arriving in Multan between August 18 and 28, Whish's army joined Edwardes army, and began the siege of Multan.

Chattar Singh and his son Sher Singh join the rebellion after humiliating treatment by junior British officers

Other British Political Agents, who took action on their own, to forestall any rebellion were Captain John Nicholson, who seized the vital fort of Attock, from its Sikh Garrison, and then subsequently linked-up his forces with James Abbott's local Hazara levies to capture the Margalla Hills, that separated Hazara from other parts of Punjab. Captain James Abbot, the assistant to the political resident at Hazara, accused the Sikh governor of the province, Chattar Singh Attariwala of conspiring to lead a general Sikh uprising against the British. An inquiry conducted into Abbott's allegations by Captain Nicholson exonerated him of the charge of treason, but relieved him of his duties as governor and confiscated his jagirs. Chattar Singh was one of the most senior and eminent Sikh chiefs, since the time of Ranjeet Singh, greatly respected by his people and whose daughter was betrothed to the young Maharajah Duleep Singh. The humiliating treatment to which such a respected Sikh chief was subjected to by two junior British officers, created two powerful enemies for the British who were previously loyal to them. They were Sikh Chief Chattar Singh Attariwala and his son Sher Singh Attariwala, who fought loyally for the British on the side of Herbert Edwards, against Diwan Mul Raj. Sher Singh Attariwala joined hands with Diwan Mul Raj on September 14, 1848. Thus the uprising which was previously localized around Multan, now spread across the whole of Punjab, and was led by the three leaders Diwan Mul Raj, Raja Sher Singh and Chattar Singh. Raja Sher Singh issued a passionate appeal to his people to rally round the leaders of the uprising to safeguard the hard won freedom of the Punjab, and many former soldiers of the Khalsa army responded to the call.

The first encounter the "Battle of Ramnagar" was a clear victory for Sher Singh's forces and a disaster for the British

Multan and Hazara became the focus of the uprising. While Diwan Mul Raj was to continue holding the City of Multan, Sher Singh with his army were to march northwards into Central Punjab, and ultimately rejoin Chattar Singh, who with his army would attempt to move downwards from Hazara. When the cold season of November approached large contingent of troops from the Bengal Army and the Bombay Army began moving towards the Punjab. While the Bombay Army moved towards Multan to reinforce the forces of Whish besieging the city, the Bengal Army led by its commander Hugh Gough moved against Sher Singh's army entrenched near Ramnagar, by the right bank of the River Chenab. Gough's army approached Ramnagar on November 22, 1848. An infantry division led by Brigadier-General Campbell and the cavalry in command of Brigadier-General Cureton, were ordered to move towards Ramnagar to disperse the Sikh force. When Campbell's forces reached Ramnagar, they found the Sikh forces on the opposite side of the River Chenab. When the Sikh troops appeared to be withdrawing from the river bank, Cureton ordered the horse artillery under Colonel Lane to overtake the withdrawing troops through the sandy river bed, but they met with disaster. The Sikh artillery on the opposite bank opened up with disastrous consequences to the horse artillery, and Lane was forced to withdraw, leaving behind a heavy gun and two ammunition wagons, that was captured by the Sikhs. The Sikhs then went on the offensive, a column of Sikh cavalry crossing the river under the cover of artillery. The charge by the Sikhs left 90 officers and men of the Bengal Army dead, that included Brigadier-General Cureton, and Lieutenant-Colonel Havelock. The battle at Ramnagar became a morale-boosting victory for the Sikhs, who were greatly outnumbered by the British forces. Dalhousie blamed both Gough and Campbell for the disaster at Ramnagar.

A second attempt by Hugh Gough to attack Sher Singh's army on the flanks thwarted by an intelligent tactical move by Sher Singh

For about a week after the British reverses, there was an uneasy calm across the frontline, the two armies facing each other across the river. Sher Singh's entire force now risen to 12,000 men and 28 guns, was strongly entrenched at the principal ford 3 km from Ramnagar. Instead of launching frontal assaults on Sher Singh's army, Gough decided to change his strategy and attack the army on the flanks. He detailed two divisions of the army, one under the command of Major-General Thackwell and the other under Brigadier Godby, to cross the River Chenab north and south of Sher Singh's positions and attack from the flanks. Thackwell's forces moved 30 km up the river and made the crossing at Wazirabad. Godby's force moved 25 km downstream and made the crossing. Thackwell's forces moved downwards, and reached Sadullapur just 6 km from the Sikh positions on December 3, 1848. Godby's forces moved upwards towards the Sikh positions. The Sikh realizing the danger to their flanks and rear, opened fire at Thackwell's position using their heavy artillery, and the Sikh Cavalry attacked Godby's forces, preventing them from joining up with Thackwell's troops. At nightfall, Sher Singh made a strategic move, ordering his entire army to cross over to the left bank of the river. Sher Singh's action nullified the British maneuver, making Gough a fool in the eyes of the British military hierarchy. Hugh Gough was severely castigated for lack of drive and initiative. Sher Singh's action on the other hand was a wise move, that subsequently enabled Chattar Singh's forces moving downwards from Hazara to join him.

The "Battle of Chillianwala" another decisive victory for Sher Singh's troops, that showed tactical moves are more important than numbers in winning a war