The Statue of Liberty History

FOUNDATION STONE LAID ON

AUGUST 5,1884 /OPENED 1886 OCTOBER 28

DETAILS OF THE STATUE

It is the tallest metal statue ever constructed, and, at the time it was completed, the tallest building in New York, 22 stories high. It stands 151 feet high and weighs 225 tons. Its arms are 42 long and its torch is 21 feet in length. Its index fingers are eight feet long and it has a 4-foot 6-inch nose. It als has been described by Jonathan Waldman, in his book called Rust: the Longest War, as a High Maintenance Lady.

Since 1886 she has stood proudly in New York Harbor, in a naturally very corrosive marine environment. A gift from "the French people to the American people," master sculptor Frederic-Auguste Bartholdi had originally envisioned this to be a new Wonder of the World to mark Egypt's Suez Canal. After history and politics got in the way, Bartholdi looked to America and saw the perfect gift to celebrate America's Centennial.

Edouard de Laboulaye, French historian and admirer of American political institutions, suggested that the French present a monument to the United States, the latter to provide pedestal and site. Bartholdi visualized a colossal statue at the entrance of New York harbor, welcoming the peoples of the world with the torch of liberty.

On Washington's Birthday, Feb. 22, 1877, Congress approved the use of a site on Bedloe's Island suggested by Bartholdi. This island of 12 acres had been owned in the 17th century by a Walloon named Isaac Bedloe. It was called Bedloe's until Aug. 3, 1956, when President Eisenhower approved a resolution of Congress changing the name to Liberty Island.

The statue was finished May 21, 1884, and formally presented to the U.S. minister to France, Levi Parsons Morton, July 4, 1884, by Ferdinand de Lesseps, head of the Franco-American Union, promoter of the Panama Canal, and builder of the Suez Canal.

On Aug. 5, 1884, the Americans laid the cornerstone for the pedestal. This was to be built on the foundations of Fort Wood, which had been erected by the government in 1811. The American committee had raised $125,000, but this was found to be inadequate. Joseph Pulitzer, owner of the New York World, appealed on Mar. 16, 1885, for general donations. By Aug. 11, 1885, he had raised $100,000.

The statue arrived dismantled, in 214 packing cases, from Rouen, France, in June 1885. The last rivet of the statue was driven Oct. 28, 1886, when Pres. Grover Cleveland dedicated the monument.

The statue weighs 450,000 lbs., or 225 tons. The copper sheeting weighs 200,000 lbs. There are 167 steps from the land level to the top of the pedestal, 168 steps inside the statue to the head, and 54 rungs on the ladder leading to the arm that holds the torch.

A $2.5 million building housing the American Museum of Immigration was opened by President Richard Nixon Sept. 26, 1972, at the base of the statue. It houses a permanent exhibition of photos, posters, and artifacts tracing the history of American immigration. The Statue of Liberty National Monument is administered by the National Park Service.

Two years of restoration work was completed before the statue's centennial celebration on July 4, 1986. Among other repairs, the multimillion dollar project included replacing the 1,600 wrought iron bands that hold the statue's copper skin to its frame, replacing its torch, and installing an elevator.

In 1984, the Statue of Liberty was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The UNESCO "Statement of Significance" describes the statue as a "masterpiece of the human spirit" that "endures as a highly potent symbol—inspiring contemplation, debate and protest—of ideals such as liberty, peace, human rights, abolition of slavery, democracy and opportunity."[164]

Construction in France

| Statue of Liberty Liberty Enlightening the World | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Liberty Island Manhattan, New York City, New York,[1] United States |

| Coordinates | 40°41′21″N 74°2′40″WCoordinates: 40°41′21″N 74°2′40″W |

| Height |

|

| Dedicated | October 28, 1886 |

| Restored | 1938, 1984–1986, 2011–2012 |

| Sculptor | Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi |

| Visitors | 3.2 million (in 2009)[2] |

| Governing body | U.S. National Park Service |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, vi |

| Designated | 1984 (8th session) |

| Reference no. | 307 |

| State Party | United States |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Designated | October 15, 1924 |

| Designated by | President Calvin Coolidge[3] |

The statue's head on exhibit at the Paris World's Fair, 1878

The head and arm had been built with assistance from Viollet-le-Duc, who fell ill in 1879. He soon died, leaving no indication of how he intended to transition from the copper skin to his proposed masonry pier.[51] The following year, Bartholdi was able to obtain the services of the innovative designer and builder Gustave Eiffel.[49] Eiffel and his structural engineer, Maurice Koechlin, decided to abandon the pier and instead build an iron truss tower. Eiffel opted not to use a completely rigid structure, which would force stresses to accumulate in the skin and lead eventually to cracking. A secondary skeleton was attached to the center pylon, then, to enable the statue to move slightly in the winds of New York Harbor and as the metal expanded on hot summer days, he loosely connected the support structure to the skin using flat iron bars[27] which culminated in a mesh of metal straps, known as "saddles", that were riveted to the skin, providing firm support. In a labor-intensive process, each saddle had to be crafted individually.[52][53] To prevent galvanic corrosion between the copper skin and the iron support structure, Eiffel insulated the skin with asbestos impregnated with shellac.[54]

Eiffel's design made the statue one of the earliest examples of curtain wall construction, in which the exterior of the structure is not load bearing, but is instead supported by an interior framework. He included two interior spiral staircases, to make it easier for visitors to reach the observation point in the crown.[55] Access to an observation platform surrounding the torch was also provided, but the narrowness of the arm allowed for only a single ladder, 40 feet (12 m) long.[56] As the pylon tower arose, Eiffel and Bartholdi coordinated their work carefully so that completed segments of skin would fit exactly on the support structure.[57] The components of the pylon tower were built in the Eiffel factory in the nearby Parisian suburb of Levallois-Perret.[58]

The change in structural material from masonry to iron allowed Bartholdi to change his plans for the statue's assembly. He had originally expected to assemble the skin on-site as the masonry pier was built; instead he decided to build the statue in France and have it disassembled and transported to the United States for reassembly in place on Bedloe's Island.[59]

In a symbolic act, the first rivet placed into the skin, fixing a copper plate onto the statue's big toe, was driven by United States Ambassador to France Levi P. Morton.[60] The skin was not, however, crafted in exact sequence from low to high; work proceeded on a number of segments simultaneously in a manner often confusing to visitors.[61] Some work was performed by contractors—one of the fingers was made to Bartholdi's exacting specifications by a coppersmith in the southern French town of Montauban.[62] By 1882, the statue was complete up to the waist, an event Barthodi celebrated by inviting reporters to lunch on a platform built within the statue.[63] Laboulaye died in 1883. He was succeeded as chairman of the French committee by Ferdinand de Lesseps, builder of the Suez Canal. The completed statue was formally presented to Ambassador Morton at a ceremony in Paris on July 4, 1884, and de Lesseps announced that the French government had agreed to pay for its transport to New York.[64] The statue remained intact in Paris pending sufficient progress on the pedestal; by January 1885, this had occurred and the statue was disassembled and crated for its ocean voyage.[65]

Richard Morris Hunt's pedestal under construction in June 1885

Design

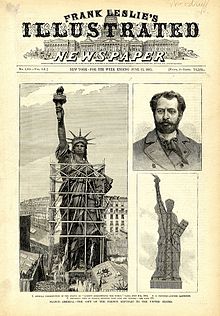

Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, June 1885, showing (clockwise from left) woodcuts of the completed statue in Paris, Bartholdi, and the statue's interior structure

Hunt's pedestal design contains elements of classical architecture, including Doric portals, as well as some elements influenced by Aztec architecture.[27] The large mass is fragmented with architectural detail, in order to focus attention on the statue.[73] In form, it is a truncated pyramid, 62 feet (19 m) square at the base and 39.4 feet (12.0 m) at the top. The four sides are identical in appearance. Above the door on each side, there are ten disks upon which Bartholdi proposed to place the coats of arms of the states (between 1876 and 1889, there were 38 U.S. states), although this was not done. Above that, a balcony was placed on each side, framed by pillars. Bartholdi placed an observation platform near the top of the pedestal, above which the statue itself rises.[74] According to author Louis Auchincloss, the pedestal "craggily evokes the power of an ancient Europe over which rises the dominating figure of the Statue of Liberty".[73] The committee hired former army General Charles Pomeroy Stone to oversee the construction work.[75] Construction on the 15-foot-deep (4.6 m) foundation began in 1883, and the pedestal's cornerstone was laid in 1884.[72] In Hunt's original conception, the pedestal was to have been made of solid granite. Financial concerns again forced him to revise his plans; the final design called for poured concrete walls, up to 20 feet (6.1 m) thick, faced with granite blocks.[76][77] This Stony Creek granite came from the Beattie Quarry in Branford, Connecticut.[78] The concrete mass was the largest poured to that time.[77]

Norwegian immigrant civil engineer Joachim Goschen Giæver designed the structural framework for the Statue of Liberty. His work involved design computations, detailed fabrication and construction drawings, and oversight of construction. In completing his engineering for the statue's frame, Giæver worked from drawings and sketches produced by Gustave Eiffel.[79]

Fundraising

Unpacking of the head of the Statue of Liberty, which was delivered on June 17, 1885

Even with these efforts, fundraising lagged. Grover Cleveland, the governor of New York, vetoed a bill to provide $50,000 for the statue project in 1884. An attempt the next year to have Congress provide $100,000, sufficient to complete the project, also failed. The New York committee, with only $3,000 in the bank, suspended work on the pedestal. With the project in jeopardy, groups from other American cities, including Boston and Philadelphia, offered to pay the full cost of erecting the statue in return for relocating it.[83]

Joseph Pulitzer, publisher of the New York World, a New York newspaper, announced a drive to raise $100,000—the equivalent of $2.3 million today.[84] Pulitzer pledged to print the name of every contributor, no matter how small the amount given.[85] The drive captured the imagination of New Yorkers, especially when Pulitzer began publishing the notes he received from contributors. "A young girl alone in the world" donated "60 cents, the result of self denial."[86] One donor gave "five cents as a poor office boy's mite toward the Pedestal Fund." A group of children sent a dollar as "the money we saved to go to the circus with."[87] Another dollar was given by a "lonely and very aged woman."[86] Residents of a home for alcoholics in New York's rival city of Brooklyn—the cities would not merge until 1898—donated $15; other drinkers helped out through donation boxes in bars and saloons.[88] A kindergarten class in Davenport, Iowa, mailed the World a gift of $1.35.[86] As the donations flooded in, the committee resumed work on the pedestal.[89]

Construction

On June 17, 1885, the French steamer Isère, laden with the Statue of Liberty, reached the New York port safely. New Yorkers displayed their new-found enthusiasm for the statue, as the French vessel arrived with the crates holding the disassembled statue on board. Two hundred thousand people lined the docks and hundreds of boats put to sea to welcome the Isère.[90] [91] After five months of daily calls to donate to the statue fund, on August 11, 1885, the World announced that $102,000 had been raised from 120,000 donors, and that 80 percent of the total had been received in sums of less than one dollar.[92]

Even with the success of the fund drive, the pedestal was not completed until April 1886. Immediately thereafter, reassembly of the statue began. Eiffel's iron framework was anchored to steel I-beams within the concrete pedestal and assembled.[93] Once this was done, the sections of skin were carefully attached.[94] Due to the width of the pedestal, it was not possible to erect scaffolding, and workers dangled from ropes while installing the skin sections. Nevertheless, no one died during the construction.[95] Bartholdi had planned to put floodlights on the torch's balcony to illuminate it; a week before the dedication, the Army Corps of Engineers vetoed the proposal, fearing that ships' pilots passing the statue would be blinded. Instead, Bartholdi cut portholes in the torch—which was covered with gold leaf—and placed the lights inside them.[96] A power plant was installed on the island to light the torch and for other electrical needs.[97] After the skin was completed, renowned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, co-designer of New York's Central Park and Brooklyn's Prospect Park, supervised a cleanup of Bedloe's Island in anticipation of the dedication.[98]

Dedication

Unveiling of the Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World (1886) by Edward Moran.

Oil on canvas. The J. Clarence Davies Collection, Museum of the City of New York.

A ceremony of dedication was held on the afternoon of October 28, 1886. President Grover Cleveland, the former New York governor, presided over the event.[99] On the morning of the dedication, a parade was held in New York City; estimates of the number of people who watched it ranged from several hundred thousand to a million. President Cleveland headed the procession, then stood in the reviewing stand to see bands and marchers from across America. General Stone was the grand marshal of the parade. The route began at Madison Square, once the venue for the arm, and proceeded to Battery Park at the southern tip of Manhattan by way of Fifth Avenue and Broadway, with a slight detour so the parade could pass in front of the World building on Park Row. As the parade passed the New York Stock Exchange, traders threw ticker tape from the windows, beginning the New York tradition of the ticker-tape parade.[100]

A nautical parade began at 12:45 p.m., and President Cleveland embarked on a yacht that took him across the harbor to Bedloe's Island for the dedication.[101] De Lesseps made the first speech, on behalf of the French committee, followed by the chairman of the New York committee, Senator William M. Evarts. A French flag draped across the statue's face was to be lowered to unveil the statue at the close of Evarts's speech, but Bartholdi mistook a pause as the conclusion and let the flag fall prematurely. The ensuing cheers put an end to Evarts's address.[100] President Cleveland spoke next, stating that the statue's "stream of light shall pierce the darkness of ignorance and man's oppression until Liberty enlightens the world".[102] Bartholdi, observed near the dais, was called upon to speak, but he refused. Orator Chauncey M. Depew concluded the speechmaking with a lengthy address.[103]

No members of the general public were permitted on the island during the ceremonies, which were reserved entirely for dignitaries. The only females granted access were Bartholdi's wife and de Lesseps's granddaughter; officials stated that they feared women might be injured in the crush of people. The restriction offended area suffragists, who chartered a boat and got as close as they could to the island. The group's leaders made speeches applauding the embodiment of Liberty as a woman and advocating women's right to vote.[102] A scheduled fireworks display was postponed until November 1 because of poor weather.[104]

Shortly after the dedication, The Cleveland Gazette, an African American newspaper, suggested that the statue's torch not be lit until the United States became a free nation "in reality":

"Liberty enlightening the world," indeed! The expression makes us sick. This government is a howling farce. It can not or rather does not protect its citizens within its own borders. Shove the Bartholdi statue, torch and all, into the ocean until the "liberty" of this country is such as to make it possible for an inoffensive and industrious colored man to earn a respectable living for himself and family, without being ku-kluxed, perhaps murdered, his daughter and wife outraged, and his property destroyed. The idea of the "liberty" of this country "enlightening the world," or even Patagonia, is ridiculous in the extreme.[105]

After dedication

Lighthouse Board and War Department (1886–1933)

Statue of Liberty ca. 1900

Government poster using the Statue of Liberty to promote the sale of Liberty Bonds

When the torch was illuminated on the evening of the statue's dedication, it produced only a faint gleam, barely visible from Manhattan. The World characterized it as "more like a glowworm than a beacon."[97] Bartholdi suggested gilding the statue to increase its ability to reflect light, but this proved too expensive. The United States Lighthouse Board took over the Statue of Liberty in 1887 and pledged to install equipment to enhance the torch's effect; in spite of its efforts, the statue remained virtually invisible at night. When Bartholdi returned to the United States in 1893, he made additional suggestions, all of which proved ineffective. He did successfully lobby for improved lighting within the statue, allowing visitors to better appreciate Eiffel's design.[97] In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt, once a member of the New York committee, ordered the statue's transfer to the War Department, as it had proved useless as a lighthouse.[106] A unit of the Army Signal Corps was stationed on Bedloe's Island until 1923, after which military police remained there while the island was under military jurisdiction.[107]

The statue rapidly became a landmark. Many immigrants who entered through New York saw it as a welcoming sight. Oral histories of immigrants record their feelings of exhilaration on first viewing the Statue of Liberty. One immigrant who arrived from Greece recalled,

I saw the Statue of Liberty. And I said to myself, "Lady, you're such a beautiful! [sic] You opened your arms and you get all the foreigners here. Give me a chance to prove that I am worth it, to do something, to be someone in America." And always that statue was on my mind.[108]

Originally, the statue was a dull copper color, but shortly after 1900 a green patina, also called verdigris, caused by the oxidation of the copper skin, began to spread. As early as 1902 it was mentioned in the press; by 1906 it had entirely covered the statue.[109] Believing that the patina was evidence of corrosion, Congress authorized $62,800 for various repairs, and to paint the statue both inside and out.[110] There was considerable public protest against the proposed exterior painting.[111] The Army Corps of Engineers studied the patina for any ill effects to the statue and concluded that it protected the skin, "softened the outlines of the Statue and made it beautiful."[112] The statue was painted only on the inside. The Corps of Engineers also installed an elevator to take visitors from the base to the top of the pedestal.[112]

On July 30, 1916, during World War I, German saboteurs set off a disastrous explosion on the Black Tom peninsula in Jersey City, New Jersey, in what is now part of Liberty State Park, close to Bedloe's Island. Carloads of dynamite and other explosives that were being sent to Britain and France for their war efforts were detonated, and seven people were killed. The statue sustained minor damage, mostly to the torch-bearing right arm, and was closed for ten days. The cost to repair the statue and buildings on the island was about $100,000. The narrow ascent to the torch was closed for public safety reasons, and it has remained closed ever since.[103]

That same year, Ralph Pulitzer, who had succeeded his father Joseph as publisher of the World, began a drive to raise $30,000 for an exterior lighting system to illuminate the statue at night. He claimed over 80,000 contributors but failed to reach the goal. The difference was quietly made up by a gift from a wealthy donor—a fact that was not revealed until 1936. An underwater power cable brought electricity from the mainland and floodlights were placed along the walls of Fort Wood. Gutzon Borglum, who later sculpted Mount Rushmore, redesigned the torch, replacing much of the original copper with stained glass. On December 2, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson pressed the telegraph key that turned on the lights, successfully illuminating the statue.[113]

After the United States entered World War I in 1917, images of the statue were heavily used in both recruitment posters and the Liberty Bond drives that urged American citizens to support the war financially. This impressed upon the public the war's stated purpose—to secure liberty—and served as a reminder that embattled France had given the United States the statue.[114]

In 1924, President Calvin Coolidge used his authority under the Antiquities Act to declare the statue a National Monument.[106] The only successful suicide in the statue's history occurred five years later, when a man climbed out of one of the windows in the crown and jumped to his death, glancing off the statue's breast and landing on the base.[115]

Early National Park Service years (1933–1982)

Bedloe's Island in 1927, showing the statue and army buildings. The eleven-pointed walls of Fort Wood, which still form the statue's base, are visible.

During World War II, the statue remained open to visitors, although it was not illuminated at night due to wartime blackouts. It was lit briefly on December 31, 1943, and on D-Day, June 6, 1944, when its lights flashed "dot-dot-dot-dash", the Morse code for V, for victory. New, powerful lighting was installed in 1944–1945, and beginning on V-E Day, the statue was once again illuminated after sunset. The lighting was for only a few hours each evening, and it was not until 1957 that the statue was illuminated every night, all night.[119] In 1946, the interior of the statue within reach of visitors was coated with a special plastic so that graffiti could be washed away.[118]

In 1956, an Act of Congress officially renamed Bedloe's Island as Liberty Island, a change advocated by Bartholdi generations earlier. The act also mentioned the efforts to found an American Museum of Immigration on the island, which backers took as federal approval of the project, though the government was slow to grant funds for it.[120] Nearby Ellis Island was made part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument by proclamation of President Lyndon Johnson in 1965.[106] In 1972, the immigration museum, in the statue's base, was finally opened in a ceremony led by President Richard Nixon. The museum's backers never provided it with an endowment to secure its future and it closed in 1991 after the opening of an immigration museum on Ellis Island.[93]

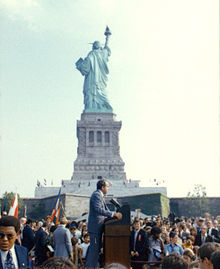

September 26, 1972: President Richard Nixon visits the statue to open the American Museum of Immigration. The statue's raised right foot is visible, showing that it is depicted moving forward.

Beginning December 26, 1971, 15 anti-Vietnam War veterans occupied the statue, flying a US flag upside down from her crown. They left December 28 following a Federal Court order.[123] The statue was also several times taken over briefly by demonstrators publicizing causes such as Puerto Rican independence, opposition to abortion, and opposition to US intervention in Grenada. Demonstrations with the permission of the Park Service included a Gay Pride Parade rally and the annual Captive Baltic Nations rally.[124]

A powerful new lighting system was installed in advance of the American Bicentennial in 1976. The statue was the focal point for Operation Sail, a regatta of tall ships from all over the world that entered New York Harbor on July 4, 1976, and sailed around Liberty Island.[125] The day concluded with a spectacular display of fireworks near the statue.[126]

Renovation and rededication (1982–2000)

July 4, 1986: First Lady Nancy Reagan (in red) reopens the statue to the public.

Main article: Restoration of the Statue of Liberty (1984–86)

The statue was examined in great detail by French and American engineers as part of the planning for its centennial in 1986.[127] In 1982, it was announced that the statue was in need of considerable restoration. Careful study had revealed that the right arm had been improperly attached to the main structure. It was swaying more and more when strong winds blew and there was a significant risk of structural failure. In addition, the head had been installed 2 feet (0.61 m) off center, and one of the rays was wearing a hole in the right arm when the statue moved in the wind. The armature structure was badly corroded, and about two percent of the exterior plates needed to be replaced.[128] Although problems with the armature had been recognized as early as 1936, when cast iron replacements for some of the bars had been installed, much of the corrosion had been hidden by layers of paint applied over the years.[129]

In May 1982, President Ronald Reagan announced the formation of the Statue of Liberty–Ellis Island Centennial Commission, led by Chrysler Corporation chair Lee Iacocca, to raise the funds needed to complete the work.[130] Through its fundraising arm, the Statue of Liberty–Ellis Island Foundation, Inc., the group raised more than $350 million in donations.[131] The Statue of Liberty was one of the earliest beneficiaries of a cause marketing campaign. A 1983 promotion advertised that for each purchase made with an American Express card, the company would contribute one cent to the renovation of the statue. The campaign generated contributions of $1.7 million to the restoration project.[132]

In 1984, the statue was closed to the public for the duration of the renovation. Workers erected the world's largest free-standing scaffold,[27] which obscured the statue from view. Liquid nitrogen was used to remove layers of paint that had been applied to the interior of the copper skin over decades, leaving two layers of coal tar, originally applied to plug leaks and prevent corrosion. Blasting with baking soda powder removed the tar without further damaging the copper.[133] The restorers' work was hampered by the asbestos-based substance that Bartholdi had used—ineffectively, as inspections showed—to prevent galvanic corrosion. Workers within the statue had to wear protective gear, dubbed "moon suits", with self-contained breathing circuits.[134] Larger holes in the copper skin were repaired, and new copper was added where necessary.[135] The replacement skin was taken from a copper rooftop at Bell Labs, which had a patina that closely resembled the statue's; in exchange, the laboratory was provided some of the old copper skin for testing.[136] The torch, found to have been leaking water since the 1916 alterations, was replaced with an exact replica of Bartholdi's unaltered torch.[137] Consideration was given to replacing the arm and shoulder; the National Park Service insisted that they be repaired instead.[138] The original torch was removed and replaced in 1986 with the current one, whose flame is covered in 24-carat gold.[30] The torch reflects the sun's rays in daytime and lighted by floodlights at night.[30]

The entire puddled iron armature designed by Gustave Eiffel was replaced. Low-carbon corrosion-resistant stainless steel bars that now hold the staples next to the skin are made of Ferralium, an alloy that bends slightly and returns to its original shape as the statue moves.[139] To prevent the ray and arm making contact, the ray was realigned by several degrees.[140] The lighting was again replaced—night-time illumination subsequently came from metal-halide lamps that send beams of light to particular parts of the pedestal or statue, showing off various details.[141] Access to the pedestal, which had been through a nondescript entrance built in the 1960s, was renovated to create a wide opening framed by a set of monumental bronze doors with designs symbolic of the renovation.[142] A modern elevator was installed, allowing handicapped access to the observation area of the pedestal.[143] An emergency elevator was installed within the statue, reaching up to the level of the shoulder.[144]

July 3–6, 1986, was designated "Liberty Weekend", marking the centennial of the statue and its reopening. President Reagan presided over the rededication, with French President François Mitterrand in attendance. July 4 saw a reprise of Operation Sail,[145] and the statue was reopened to the public on July 5.[146] In Reagan's dedication speech, he stated, "We are the keepers of the flame of liberty; we hold it high for the world to see."[145]

Closures and reopenings (2001–present)

The Statue of Liberty on September 11, 2001 as the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center burn in the background

The statue, including the pedestal and base, closed on October 29, 2011, for installation of new elevators and staircases and to bring other facilities, such as restrooms, up to code. The statue was reopened on October 28, 2012,[1][149][150] only to close again a day later due to Hurricane Sandy.[151] Although the storm did not harm the statue, it destroyed some of the infrastructure on both Liberty Island and Ellis Island, severely damaging the dock used by the ferries bearing visitors to the statue. On November 8, 2012, a Park Service spokesperson announced that both islands would remain closed for an indefinite period for repairs to be done.[152] Due to lack of electricity on Liberty Island, a generator was installed to power temporary floodlights to illuminate the statue at night. The superintendent of Statue of Liberty National Monument, David Luchsinger, whose home on the island was severely damaged, stated that it would be "optimistically ... months" before the island was reopened to the public.[153] The statue and Liberty Island reopened to the public on July 4, 2013.[154] Ellis Island remained closed for repairs for several more months but reopened in late October 2013.[155] For part of October 2013, Liberty Island was closed to the public due to the United States federal government shutdown of 2013, along with other federally funded museums, parks, monuments, construction projects and buildings.[156]

On October 7, 2016, construction started on a new Statue of Liberty museum on Liberty Island. The new $70 million, 26,000-square-foot (2,400 m2) museum will be able to accommodate all of the island's visitors when it opens in 2019, as opposed to the current museum, which only 20% of the island's visitors can visit.[157] The original torch will be relocated here, and in addition to exhibits relating to the statue's construction and history, there will be a theater where visitors can watch an aerial view of the statue.[157][158] The museum, designed by FXFOWLE Architects, will integrate with the parkland around it.[158] It is being funded privately by Diane von Fürstenberg, Michael Bloomberg, Jeff Bezos, Coca-Cola, NBCUniversal, the family of Laurence Tisch and Preston Robert Tisch, and Mellody Hobson and George Lucas.[159] Von Fürstenberg heads the fundraising for the museum, and the project had garnered more than $40 million in fundraising as of groundbreaking.[158]

Access and attributes

Location and tourism

Tourists aboard a Circle Line ferry arriving at Liberty Island, June 1973

No charge is made for entrance to the national monument, but there is a cost for the ferry service that all visitors must use, as private boats may not dock at the island. A concession was granted in 2007 to Statue Cruises to operate the transportation and ticketing facilities, replacing Circle Line, which had operated the service since 1953.[162] The ferries, which depart from Liberty State Park in Jersey City and Battery Park in Lower Manhattan, also stop at Ellis Island when it is open to the public, making a combined trip possible.[163] All ferry riders are subject to security screening, similar to airport procedures, prior to boarding.[164] Visitors intending to enter the statue's base and pedestal must obtain a complimentary museum/pedestal ticket along with their ferry ticket.[165] Those wishing to climb the staircase within the statue to the crown purchase a special ticket, which may be reserved up to a year in advance. A total of 240 people per day are permitted to ascend: ten per group, three groups per hour. Climbers may bring only medication and cameras—lockers are provided for other items—and must undergo a second security screening.[166]

Inscriptions, plaques, and dedications

The Statue of Liberty stands on Liberty Island.

A plaque on the copper just under the figure in front declares that it is a colossal statue representing Liberty, designed by Bartholdi and built by the Paris firm of Gaget, Gauthier et Cie (Cie is the French abbreviation analogous to Co.). [167]

A presentation tablet, also bearing Bartholdi's name, declares the statue is a gift from the people of the Republic of France that honors "the Alliance of the two Nations in achieving the Independence of the United States of America and attests their abiding friendship."[167]

A tablet placed by the New York committee commemorates the fundraising done to build the pedestal.[167]

The cornerstone bears a plaque placed by the Freemasons.[167]

In 1903, a bronze tablet that bears the text of Emma Lazarus's sonnet, "The New Colossus" (1883), was presented by friends of the poet. Until the 1986 renovation, it was mounted inside the pedestal; today it resides in the Statue of Liberty Museum, in the base.[167]

"The New Colossus" tablet is accompanied by a tablet given by the Emma Lazarus Commemorative Committee in 1977, celebrating the poet's life.[167]

A group of statues stands at the western end of the island, honoring those closely associated with the Statue of Liberty. Two Americans—Pulitzer and Lazarus—and three Frenchmen—Bartholdi, Eiffel, and Laboulaye—are depicted. They are the work of Maryland sculptor Phillip Ratner.[

No comments:

Post a Comment