ABOLITION OF SLAVERY IN USA

13 TH AMENDMENT TOOK EFFECT

FROM 1865,DECEMBER 18

The Thirteenth Amendment (Amendment XIII) to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. In Congress, it was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, and by the House on January 31, 1865.

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States of America |

|---|

|

| Preamble and Articles of the Constitution |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

|

| Unratified Amendments |

| History |

| Full text of the Constitution and Amendments |

Since the American Revolution, states had divided into states that allowed and states that prohibited slavery. Slavery had been tacitly enshrined in the original Constitution through provisions such as Article I, Section 2, Clause 3, commonly known as the Three-Fifths Compromise, which detailed how each slave state's enslaved population would be factored into its total population count for the purposes of apportioning seats in the United States House of Representatives and direct taxes among the states. Though many slaves had been declared free by President Abraham Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, their post-war status was uncertain. On April 8, 1864, the Senate passed an amendment to abolish slavery. After one unsuccessful vote and extensive legislative maneuvering by the Lincoln administration, the House followed suit on January 31, 1865. The measure was swiftly ratified by nearly all Northern states, along with a sufficient number of border and "reconstructed" Southern states, to cause it to be adopted before the end of the year.

Though the amendment formally abolished slavery throughout the United States, factors such as Black Codes, white supremacist violence, and selective enforcement of statutes continued to subject some black Americans to involuntary labor, particularly in the South. In contrast to the other Reconstruction Amendments, the Thirteenth Amendment was rarely cited in later case law, but has been used to strike down peonage and some race-based discrimination as "badges and incidents of slavery". The Thirteenth Amendment applies to the actions of private citizens, while the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments apply only to state actors. The amendment also enables Congress to pass laws against sex trafficking and other modern forms of slavery.

Slavery in the United States

Main article: Slavery in the United States

The institution of slavery existed in all of the original thirteen British North American colonies. Prior to the Thirteenth Amendment, the United States Constitution (adopted in 1789) did not expressly use the words slave or slavery but included several provisions about unfree persons. The Three-Fifths Clause (in Article I, Section 2) allocated Congressional representation based "on the whole Number of free Persons" and "three fifths of all other Persons". This clause was a compromise between Southerners who wished slaves to be counted as 'persons' for congressional representation and northerners rejecting these out of concern of too much power for the South, because representation in the new Congress would be based on population in contrast to the one-vote-for-one-state principle in the earlier Continental Congress.[3] Under the Fugitive Slave Clause (Article IV, Section 2), "No person held to Service or Labour in one State" would be freed by escaping to another. Article I, Section 9 allowed Congress to pass legislation outlawing the "Importation of Persons", but not until 1808. However, for purposes of the Fifth Amendment—which states that, "No person shall... be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law"—slaves were understood as property.[4] Although abolitionists used the Fifth Amendment to argue against slavery, it became part of the legal basis for treating slaves as property with Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857).[5]

Stimulated by the philosophy of the Declaration of Independence between 1777 and 1804, every Northern state provided for the immediate or gradual abolition of slavery. Most of the slaves involved were household servants. No Southern state did so, and the slave population of the South continued to grow, peaking at almost 4 million people in 1861. An abolitionist movement headed by such figures as William Lloyd Garrison grew in strength in the North, calling for the end of slavery nationwide and exacerbating tensions between North and South. The American Colonization Society, an alliance between abolitionists who felt the races should be kept separated and slaveholders who feared the presence of freed blacks would encourage slave rebellions, called for the emigration and colonization of both free blacks and slaves to Africa. Its views were endorsed by politicians such as Henry Clay, who feared that the main abolitionist movement would provoke a civil war.[6] Proposals to eliminate slavery by constitutional amendment were introduced by Representative Arthur Livermore in 1818 and by John Quincy Adams in 1839, but failed to gain significant traction.[7]

Stimulated by the philosophy of the Declaration of Independence between 1777 and 1804, every Northern state provided for the immediate or gradual abolition of slavery. Most of the slaves involved were household servants. No Southern state did so, and the slave population of the South continued to grow, peaking at almost 4 million people in 1861. An abolitionist movement headed by such figures as William Lloyd Garrison grew in strength in the North, calling for the end of slavery nationwide and exacerbating tensions between North and South. The American Colonization Society, an alliance between abolitionists who felt the races should be kept separated and slaveholders who feared the presence of freed blacks would encourage slave rebellions, called for the emigration and colonization of both free blacks and slaves to Africa. Its views were endorsed by politicians such as Henry Clay, who feared that the main abolitionist movement would provoke a civil war.[6] Proposals to eliminate slavery by constitutional amendment were introduced by Representative Arthur Livermore in 1818 and by John Quincy Adams in 1839, but failed to gain significant traction.[7]As the country continued to expand, the issue of slavery in its new territories became the dominant national issue. The Southern position was that slaves were property and therefore could be moved to the territories like all other forms of property.[8] The 1820 Missouri Compromise provided for the admission of Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, preserving the Senate's equality between the regions. In 1846, the Wilmot Proviso was introduced to a war appropriations bill to ban slavery in all territories acquired in the Mexican–American War; the Proviso repeatedly passed the House, but not the Senate.[8] The Compromise of 1850 temporarily defused the issue by admitting California as a free state, instituting a stronger Fugitive Slave Act, banning the slave trade in Washington, D.C., and allowing New Mexico and Utah self-determination on the slavery issue.[9]

Despite the compromise, tensions between North and South continued to rise over the subsequent decade, inflamed by, amongst other things, the publication of the 1852 anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin; fighting between pro-slave and abolitionist forces in Kansas, beginning in 1854; the 1857 Dred Scott decision, which struck down provisions of the Compromise of 1850; abolitionist John Brown's 1859 attempt to start a slave revolt at Harpers Ferry and the 1860 election of slavery critic Abraham Lincoln to the presidency. The Southern states seceded from the Union in the months following Lincoln's election, forming the Confederate States of America, and beginning the American Civil War.

Despite the compromise, tensions between North and South continued to rise over the subsequent decade, inflamed by, amongst other things, the publication of the 1852 anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin; fighting between pro-slave and abolitionist forces in Kansas, beginning in 1854; the 1857 Dred Scott decision, which struck down provisions of the Compromise of 1850; abolitionist John Brown's 1859 attempt to start a slave revolt at Harpers Ferry and the 1860 election of slavery critic Abraham Lincoln to the presidency. The Southern states seceded from the Union in the months following Lincoln's election, forming the Confederate States of America, and beginning the American Civil War.Proposal and ratification

Crafting the amendment

Representative James Mitchell Ashley proposed an amendment abolishing slavery in 1863.

In the final years of the Civil War, Union lawmakers debated various proposals for Reconstruction.[13] Some of these called for a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery nationally and permanently. On December 14, 1863, a bill proposing such an amendment was introduced by Representative James Mitchell Ashley of Ohio.[14][15] Representative James F. Wilson of Iowa soon followed with a similar proposal. On January 11, 1864, Senator John B. Henderson of Missouri submitted a joint resolution for a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. The Senate Judiciary Committee, chaired by Lyman Trumbull of Illinois, became involved in merging different proposals for an amendment.

Radical Republicans led by Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner and Pennsylvania Representative Thaddeus Stevens sought a more expansive version of the amendment.[16] On February 8, 1864, Sumner submitted a constitutional amendment stating:

Radical Republicans led by Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner and Pennsylvania Representative Thaddeus Stevens sought a more expansive version of the amendment.[16] On February 8, 1864, Sumner submitted a constitutional amendment stating:All persons are equal before the law, so that no person can hold another as a slave; and the Congress shall have power to make all laws necessary and proper to carry this declaration into effect everywhere in the United States.[17][18]

Sumner tried to promote his own more expansive wording by circumventing the Trumbull-controlled Judiciary Committee, but failed.[19] On February 10, the Senate Judiciary Committee presented the Senate with an amendment proposal based on drafts of Ashley, Wilson and Henderson.[20][21]

The Committee's version used text from the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which stipulates, "There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted."[22][23]:1786 Though using Henderson's proposed amendment as the basis for its new draft, the Judiciary Committee removed language that would have allowed a constitutional amendment to be adopted with only a majority vote in each House of Congress and ratification by two-thirds of the states (instead of two-thirds and three-fourths, respectively).[24]

Passage by Congress

Further information: 38th United States Congress

Further information: 38th United States CongressThe Senate passed the amendment on April 8, 1864, by a vote of 38 to 6; two Democrats, Reverdy Johnson of Maryland and James Nesmith of Oregon voted "aye." However, just over two months later on June 15, the House failed to do so, with 93 in favor and 65 against, thirteen votes short of the two-thirds vote needed for passage; the vote split largely along party lines, with Republicans supporting and Democrats opposing.[25] In the 1864 presidential race, former Free Soil Party candidate John C. Frémont threatened a third-party run opposing Lincoln, this time on a platform endorsing an anti-slavery amendment. The Republican Party platform had, as yet, failed to include a similar plank, though Lincoln endorsed the amendment in a letter accepting his nomination.[26][27] Fremont withdrew from the race on September 22, 1864 and endorsed Lincoln.[28]

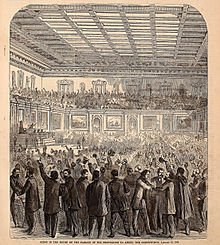

Celebration erupts after the amendment is passed by the House of Representatives.

Republicans portrayed slavery as uncivilized and argued for abolition as a necessary step in national progress.[32] Amendment supporters also argued that the slave system had negative effects on white people. These included the lower wages resulting from competition with forced labor, as well as repression of abolitionist whites in the South. Advocates said ending slavery would restore the First Amendment and other constitutional rights violated by censorship and intimidation in slave states.[31][33]

White Northern Republicans, and some Democrats, became excited about an abolition amendment, holding meetings and issuing resolutions.[34] Many blacks, particularly in the South, focused more on landownership and education as the key to liberation.[35] As slavery began to seem politically untenable, an array of Northern Democrats successively announced their support for the amendment, including Representative James Brooks,[36] Senator Reverdy Johnson,[37] and Tammany Hall, a powerful New York political machine.[38]

White Northern Republicans, and some Democrats, became excited about an abolition amendment, holding meetings and issuing resolutions.[34] Many blacks, particularly in the South, focused more on landownership and education as the key to liberation.[35] As slavery began to seem politically untenable, an array of Northern Democrats successively announced their support for the amendment, including Representative James Brooks,[36] Senator Reverdy Johnson,[37] and Tammany Hall, a powerful New York political machine.[38]Celebration erupts after the amendment is passed by the House of Representatives.

President Lincoln had had concerns that the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 might be reversed or found invalid after the war. He saw constitutional amendment as a more permanent solution.[39][40] He had remained outwardly neutral on the amendment because he considered it politically too dangerous.[41] Nonetheless, Lincoln's 1864 party platform resolved to abolish slavery by constitutional amendment.[42][43] After winning the election of 1864, Lincoln made the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment his top legislative priority, beginning his efforts while the "lame duck" session was still in office.[44][45] Popular support for the amendment mounted and Lincoln urged Congress on in his December 6 State of the Union speech: "there is only a question of time as to when the proposed amendment will go to the States for their action. And as it is to so go, at all events, may we not agree that the sooner the better?"[46]

Lincoln instructed Secretary of State William H. Seward, Representative John B. Alley and others to procure votes by any means necessary, and they promised government posts and campaign contributions to outgoing Democrats willing to switch sides.[47][48] Seward had a large fund for direct bribes. Ashley, who reintroduced the measure into the House, also lobbied several Democrats to vote in favor of the measure.[49] Representative Thaddeus Stevens commented later that "the greatest measure of the nineteenth century was passed by corruption, aided and abetted by the purest man in America"; however, Lincoln's precise role in making deals for votes remains unknown.[50]

Lincoln instructed Secretary of State William H. Seward, Representative John B. Alley and others to procure votes by any means necessary, and they promised government posts and campaign contributions to outgoing Democrats willing to switch sides.[47][48] Seward had a large fund for direct bribes. Ashley, who reintroduced the measure into the House, also lobbied several Democrats to vote in favor of the measure.[49] Representative Thaddeus Stevens commented later that "the greatest measure of the nineteenth century was passed by corruption, aided and abetted by the purest man in America"; however, Lincoln's precise role in making deals for votes remains unknown.[50]Republicans in Congress claimed a mandate for abolition, having gained in the elections for Senate and House.[51] The 1864 Democratic vice-presidential nominee, Representative George H. Pendleton, led opposition to the measure.[52] Republicans toned down their language of radical equality in order to broaden the amendment's coalition of supporters.[53] In order to reassure critics worried that the amendment would tear apart the social fabric, some Republicans explicitly promised that the amendment would leave patriarchy intact.[54]

In mid-January 1865, Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax estimated the amendment to be five votes short of passage. Ashley postponed the vote.[55] At this point, Lincoln intensified his push for the amendment, making direct emotional appeals to particular members of Congress.[56] On January 31, 1865, the House called another vote on the amendment, with neither side being certain of the outcome. With 183 House members present, 122 would have to vote "aye" to secure passage of the resolution; however eight members abstained, reducing the number to 117. Every Republican supported the measure, as well as 16 Democrats, almost all of them lame ducks. The amendment finally passed by a vote of 119 to 56,[57] narrowly reaching the required two-thirds majority.[58] The House exploded into celebration, with some members openly weeping.[59] Black onlookers, who had only been allowed to attend Congressional sessions since the previous year, cheered from the galleries.[60]

While under the Constitution, the President plays no formal role in the amendment process, the joint resolution was sent to Lincoln for his signature.[61] Under the usual signatures of the Speaker of the House and the President of the Senate, President Lincoln wrote the word "Approved" and added his signature to the joint resolution on February 1, 1865.[62] On February 7, Congress passed a resolution affirming that the Presidential signature was unnecessary.[63] The Thirteenth Amendment is the only ratified amendment signed by a President, although James Buchanan had signed the Corwin Amendment that the 36th Congress had adopted and sent to the states in March 1861.[64][65]

While under the Constitution, the President plays no formal role in the amendment process, the joint resolution was sent to Lincoln for his signature.[61] Under the usual signatures of the Speaker of the House and the President of the Senate, President Lincoln wrote the word "Approved" and added his signature to the joint resolution on February 1, 1865.[62] On February 7, Congress passed a resolution affirming that the Presidential signature was unnecessary.[63] The Thirteenth Amendment is the only ratified amendment signed by a President, although James Buchanan had signed the Corwin Amendment that the 36th Congress had adopted and sent to the states in March 1861.[64][65]Ratification by the states

When the Thirteenth Amendment was submitted to the states on February 1, 1865, it was quickly taken up by several legislatures. By the end of the month it had been ratified by eighteen states. Among them were the ex-Confederate states of Virginia and Louisiana, where ratifications were submitted by Reconstruction governments. These, along with subsequent ratifications from Arkansas and Tennessee raised the issues of how many seceded states had legally valid legislatures; and if there were fewer legislatures than states, if Article V required ratification by three-fourths of the states or three-fourths of the legally valid state legislatures.[66] President Lincoln in his last speech, on April 11, 1865, called the question about whether the Southern states were in or out of the Union a "pernicious abstraction." Obviously, he declared, they were not "in their proper practical relation with the Union"; whence everyone's object should be to restore that relation.[67] Lincoln was assassinated three days later.

With Congress out of session, the new President, Andrew Johnson, began a period known as "Presidential Reconstruction", in which he personally oversaw the creation of new state governments throughout the South. He oversaw the convening of state political conventions populated by delegates whom he deemed to be loyal. Three leading issues came before the conventions: secession itself, the abolition of slavery, and the Confederate war debt. Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, and South Carolina held conventions in 1865, while Texas' convention did not organize until March 1866.[68][69][70] Johnson hoped to prevent deliberation over whether to re-admit the Southern states by accomplishing full ratification before Congress reconvened in December. He believed he could silence those who wished to deny the Southern states their place in the Union by pointing to how essential their assent had been to the successful ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment.[71]

Slavery

IJzeren voetring voor gevangenen transparent background.png

Contemporary[show]

Historical[show]

By country or region[show]

Religion[show]

Ratified amendment, 1865

Ratified amendment post-enactment, 1865–1870

Ratified amendment after first rejecting amendment, 1866–1995

Related[show]

v t e

Direct negotiations between state governments and the Johnson administration ensued. As the summer wore on, administration officials began including assurances of the measure's limited scope with their demands for ratification. Johnson himself suggested directly to the governors of Mississippi and North Carolina that they could proactively control the allocation of rights to freedmen. Though Johnson obviously expected the freed people to enjoy at least some civil rights, including, as he specified, the right to testify in court, he wanted state lawmakers to know that the power to confer such rights would remain with the states.[72] When South Carolina provisional governor Benjamin Franklin Perry objected to the scope of the amendment's enforcement clause, Secretary of State Seward responded by telegraph that in fact the second clause "is really restraining in its effect, instead of enlarging the powers of Congress".[72] White politicians throughout the South were concerned that Congress might cite the amendment's enforcement powers as a way to authorize black suffrage.[73]

When South Carolina ratified the amendment in November 1865, it issued its own interpretive declaration that "any attempt by Congress toward legislating upon the political status of former slaves, or their civil relations, would be contrary to the Constitution of the United States".[23]:1786–1787[74] Alabama and Louisiana also declared that their ratification did not imply federal power to legislate on the status of former slaves.[23]:1787[75] During the first week of December, North Carolina and Georgia gave the amendment the final votes needed for it to become part of the Constitution.

The Thirteenth Amendment became part of the Constitution on December 6, 1865, based on the following ratifications:[76]

Illinois — February 1, 1865

Rhode Island — February 2, 1865

Michigan — February 3, 1865

Maryland — February 3, 1865

New York — February 3, 1865

Pennsylvania — February 3, 1865

West Virginia — February 3, 1865

Missouri — February 6, 1865

Maine — February 7, 1865

Kansas — February 7, 1865

Massachusetts — February 7, 1865

Virginia — February 9, 1865

Ohio — February 10, 1865

Indiana — February 13, 1865

Nevada — February 16, 1865

Louisiana — February 17, 1865

Minnesota — February 23, 1865

Wisconsin — February 24, 1865

Vermont — March 8, 1865

Tennessee — April 7, 1865

Arkansas — April 14, 1865

Connecticut — May 4, 1865

New Hampshire — July 1, 1865

South Carolina — November 13, 1865

Alabama — December 2, 1865

North Carolina — December 4, 1865

Georgia — December 6, 1865

Having been ratified by the legislatures of three-fourths of the several states (27 of the 36 states, including those that had been in rebellion), Secretary of State Seward, on December 18, 1865, certified that the Thirteenth Amendment had become valid, to all intents and purposes, as a part of the Constitution.[77] Included on the enrolled list of ratifying states were the three ex-Confederate states that had given their assent, but with strings attached. Seward accepted their affirmative votes and brushed aside their interpretive declarations without comment, challenge or acknowledgment.[78]

The Thirteenth Amendment was subsequently ratified by:[76]

Oregon — December 8, 1865

California — December 19, 1865

Florida — December 28, 1865 (Reaffirmed – June 9, 1869)

Iowa — January 15, 1866

New Jersey — January 23, 1866 (After rejection – March 16, 1865)

Texas — February 18, 1870

Delaware — February 12, 1901 (After rejection – February 8, 1865)

Kentucky — March 18, 1976[79] (After rejection – February 24, 1865)

Mississippi — March 16, 1995; Certified – February 7, 2013[80] (After rejection – December 5, 1865)

The Thirteenth Amendment became part of the Constitution 61 years after the Twelfth Amendment. This is the longest interval between constitutional amendments.[8

அடிமை ஒழிப்பு பிரகடனம் - அமெரிக்காவில் அடிமை முறை ஒழிப்பு நடைமுறைக்கு வந்த நாள் 1865 டிசம்பர் 18

செப்டம்பர் 22, 1862ல் ஜனாதிபதி ஆபிரகாம் லிங்கன் அடிமை ஒழிப்பு பிரகடனத்தைப் பகிரங்கமாக அறிவித்தார். அது ஜனவரி 1, 1863ல் இருந்து நடைமுறைக்கு வந்தபோது, நிறைவேற்று கட்டளை எழுச்சியாளர்கள் வசம் இருந்த அமெரிக்காவின் தெற்குப் பகுதிகளில் இருந்த கிட்டத்தட்ட 4 மில்லியன் அடிமைகளை சட்டபூர்வமாக சுதந்திரமாக்கியது.

அடிமை ஒழிப்பு பிரகடனம் உள்நாட்டுப் போரை ஒரு சமூகப் புரட்சியாக மாற்றியது. அதுவரை 1860ல் இருந்தபடி ஒன்றியத்தைத் தக்கவைப்பதற்காக வடக்குப் பகுதி நடத்திய போர், அடிமை முறையை அழிப்பதற்காகவும் அது அடித்தளமாகக் கொண்டிருந்த அரசியல் ஒழுங்கமைப்பை அழிப்பதற்கான போராகவும் மாற்றியது.

அதன் மகத்தான தன்மையும் லிங்கனின் நன்கு அறியப்பட்ட உரைநடை மேதை என்ற புகழும் இருக்கும்போது, இந்த ஆவணத்தின் அதிக வனப்பற்ற, சட்டபூர்வ வடிவம் வியப்பானதாகத் தோன்றலாம். முக்கியமான பத்தி ஆவணத்தின் நடுவேதான் வருகிறது. அங்கு லிங்கன் எழுதுகிறார், “நம் இறைவனின் ஆயிரத்து எண்ணுற்று அறுபத்து மூன்றாம் ஆண்டின் ஜனவரி முதலாம் நாள், எந்த மாநிலத்திலும் அல்லது மாநிலத்தில் குறிப்பிட்ட பகுதிகளிலும் அடிமைகளாக வைக்கப்பட்டுள்ளவர்கள், அமெரிக்காவிற்கு எதிராக இதையொட்டி எழுச்சி செய்திருக்கும் மாநிலங்களில், அதற்குப் பின், எப்பொழுதும் சுதந்திரமாக இருப்பர்.”

இந்த நிதானமான எழுத்துநடை பிரகடனத்தின் புரட்சிகரப் பொருளுரையைக் குறைத்துவிடவில்லை. “வரலாற்றின் போக்கில், லிங்கன் ஒரு பிரத்தியேகமான மனிதர்” என்று கார்ல் மார்க்ஸ் அக்டோபர் 9, 1862 ல் Die Presseல் குறிப்பிட்டிருந்தார். “இந்த மிகவும் பிரமிக்கத்தக்க ஆணைகள் எப்பொழுதும் அவை சிறப்பான வரலாற்று ஆவணங்களாகவே நிலைத்து நிற்கும். அவரால் எதிர்த்தரப்புக்குக் கொடுக்கப்பட்டவை அனைத்தும் ஒன்றாகத் தோன்றும், அவ்வாறு தோன்றவேண்டும் என்ற நோக்கம்தான் இருந்தது, ஒரு வக்கீல் மற்றொரு வக்கீலுக்கு வாடிக்கையாக அனுப்பும் முன்னறிவிப்பு போல்.”

சில சமயம் அழைக்கப்படுவதுபோல் இந்த “முதல்கட்ட” அடிமை ஒழிப்பு பிரகடனம் கிளர்ச்சி செய்யும் மாநிலங்களுக்கு செப்டம்பர் 22, 1862 ல் இருந்து ஜனவரி 1, 1863க்கு இடைப்பட்ட 100 நாட்களில் ஒன்றியத்திற்குத் திரும்பும் வாய்ப்பு அளித்து, அவர்கள் படிப்படியாக அடிமை முறையை அகற்றினால், அபகரித்தல் ஏற்படாது என்ற நிலையைச் சுட்டிக்காட்டியது. தன்னுடைய ஆரம்பப் பதிப்பில் லிங்கன் விடுதலையாகிவிட்ட அடிமைகள் “இந்த கண்டத்தில் அல்லது வேறிடத்தில்” ஒரு குடியேற்றத் திட்டத்திற்கு உட்படுத்தப்படலாம் என்றுகூடக் கருதினார்.

இத்தகைய ஊக்கமளித்தல் கிளர்ச்சி செய்யும் மாநிலங்களை ஒன்றியத்திற்குள் மீண்டும் கொண்டுவருவதில் வெற்றி அடையும் என்று லிங்கன் நம்பவில்லை. ஆவணத்தில் அவை சேர்க்கப்பட்டது (இறுதிப் பிரகடனத்தில் குடியேற்றத் திட்டங்கள் பற்றி லிங்கன் குறிப்பு ஏதும் கொடுக்கவில்லை) அடிமைகள் வைத்திருக்கும் எல்லை மாநிலங்களுக்கு, ஒன்றியத்தில் இருந்தவற்றிற்கு (மிசௌரி, கென்டக்கி, டிலாவர், மேற்கு வேர்ஜீனியா மற்றும் மேரிலாந்த்) மற்றும் வடக்கே வாக்காளர்களில் ஒரு பிரிவிற்கு (மக்கள் ஜனநாயகக் கட்சிச் செய்தி ஊடகம் அரசியல் வாதிகளால் இடைவிடாப் பிரச்சாரத்திற்கு “கறுப்புக் குடியரசுக் கட்சியின்” நோக்கம் “மாற்று இனங்களுக்கு இடையே திருமண உறவு கொண்டுவருதல்”, “அடிமைகளுக்கு ஏற்றம் கொடுத்தல்” என்று இருந்தவற்றின் தீவிரத்தைக் குறைக்கும் நோக்கம் கொண்டது.

தலைமைத் தளபதி என்னும் முறையில் லிங்கன் ஒரு இராணுவக் கட்டளையாக அடிமை ஒழிப்பு பிரகடனத்தை வெளியிட்டார். இவ்வடிமை ஒழிப்பிற்கு ஜனநாயகக் கட்சியின் எதிர்ப்பைச் சுற்றிக் கடக்கும் வகையில் அவர் தன்னுடைய போர்க்கால அதிகாரங்களை பயன்படுத்தினார். இக்காரணத்தையொட்டியும், அடிமை முறைக்கு இசைவு கொடுத்திருந்த அரசியலமைப்பு விதிகள் இருந்த நிலையிலும், பிரகடனம் அப்பொழுது எழுச்சி செய்திருந்த பகுதிகளுக்கு மட்டுமே பொருந்தியது. ஆனால் இந்த ஆவணம் அடிமை முறைக்கு அழிவுகாலம் என்பது குறித்து அந்நேரத்தில் சந்தேகம் எதையும் கொடுக்கவில்லை. கூட்டமைப்பின் தலைவரான ஜெபர்சன் டேவிஸ் இது “எஜமார்களை.....படுகொலை செய்வதற்கான பொது அழைப்பிதழ் இது” என்று கொதித்துக் கூறினார்.

உண்மையில் அரசியலமைப்பிற்கு 13வது திருத்தம், அமெரிக்காவில் அடிமை முறையை அகற்றியது, குடியரசுக் கட்சியின் கட்டுப்பாட்டின்கீழ் இருந்த காங்கிரசின் இரு பிரிவுகளிலும் போருக்கு முன்னதாக இயற்றப்பட்ட, உத்தியோகபூர்வமாக டிசம்பர் 1865ல் செயலுக்கு வந்தது.

அடிமை முறைக்கு லிங்கன் தனிப்பட்ட முறையில் கொண்டிருந்த எதிர்ப்பு நன்கு தெரிந்தே. நண்பர்கள், விரோதிகள் என்று அனைவராலும் அவர் அடிமை எதிர்ப்பு அரசியல்வாதி என்றுதான் காணப்பட்டார்—அகற்றிவிடுவார் என்று காணப்படவில்லை என்றாலும். “நான் ஓர் அடிமையாக இருக்க விரும்பமாட்டேன் என்பதால், நான் ஒரு எஜமானனாகவும் இருக்க மாட்டேன். இதுதான் ஜனநாயகம் பற்றிய என்னுடைய சிந்தனை” என்று லிங்கன் கூறினார்.

ஆயினும்கூட 1860 தேர்தலை ஏற்கனவே இருக்கும் இடங்களில் அடிமை முறை அகற்றப்பட மாட்டாது என்றும் புதிய பகுதிகளில்தான் தடைக்கு உட்படுத்தப்படும் என்று உறுதியளித்த அரங்கில்தான் குடியரசுக் கட்சி வெற்றி பெற்றது. தெற்கு உயரடுக்கின் இந்நிலைப்பாடு குறித்து பிரிவினை, போர் என்ற வகையில் வன்முறை நிராகரிப்பு இருந்தபோதிலும்கூட, லிங்கனின் நிர்வாகம் 1861-62 உள்நாட்டுப் போரை முன்பு இருந்த நிலைக்கும் திரும்புவதற்கான ஒரு போராகத்தான் நடத்தியது.

1862 ஆகஸ்ட் 24ம் திகதி கூட லிங்கன் வில்லியம் லோயிட் காரிசனின் அடிமை முறை அகற்றப்பட வேண்டும் எனக்கூறும் The Liberator வெளியிட்ட கடிதம் ஒன்றில் தன் நிலைப்பாட்டை மறு உறுதி செய்தது போல் தோன்றியது. புகழ் பெற்ற முறையில் அவர் எழுதினார்: “ஒரு அடிமையையும் விடுவிக்காமல் நான் ஒன்றியத்தைக் காக்க முடியும் என்றால், நான் அதைச் செய்வேன்; அனைத்து அடிமைகளையும் விடுவித்துக் காப்பாற்ற முடியும் என்றால், அதை நான் செய்வேன். ஒரு சிலரை விடுவித்து, ஒரு சிலரைப் பொருட்படுத்தமுடியாமல் காப்பாற்ற முடியும் என்றால், அதையும் நான் செய்வேன்.”

சிலர் இச்சொற்களைத் தனியே எடுத்து லிங்கன் அடிமை முறை பற்றி அதிகம் கவலைப்படவில்லை, அடிமைகளைப் பற்றியும் அதிகம் கவலைப்படவில்லை என்பதற்குச் சான்று என மேற்கோளிடுகின்றனர். ஆனால் கடிதத்தின் முடிவுப் பகுதியை அவர்கள் வசதியாக விட்டுவிடுகின்றனர். “என்னுடைய உத்தியோகபூர்வக் கடமை என்னும் பார்வையில் என் நோக்கத்தை நான் கூறியுள்ளேன்; தனிப்பட்ட முறையில் நான் அடிக்கடி கூறும் அனைத்து மக்களும் எல்லா இடங்களிலும் சுதந்திரமாக இருக்கலாம் என்பதை நான் மாற்ற விரும்பவில்லை.”

இன்னும் முக்கியமாக, அவர்கள் லிங்கன் இதற்கு முன்னரே, இரண்டு மாதங்களுக்கு முன்பே, விடுதலைப் பிரகடனத்தின் வரைவை எழுதிவிட்டார் என்ற உண்மையைக் கவனிக்கவில்லை. இப்பார்வையில், லிங்கன் காரிசனுக்கு எழுதிய கடிதம் வேறு பொருளைத்தான் கொடுக்கிறது. அவர் இப்பொழுது “ஒன்றியத்தை” “அனைத்து அடிமைகளையும் விடுவிப்பதின் மூலம்” பாதுகாக்க தயாராக இருக்கிறார் என்று காட்டுகிறார். இக்கடிதத்தின் மூலம் ஒரு பிரகடனம் அதைத்தான் செய்யும் என்பதற்கு பொதுமக்களை தயார்ப்படுத்துகிறார்.

ஆனால் ஒன்றியத்தின் நீண்ட போரில் அதிக வெற்றி இல்லாத கட்டங்களில் ஒன்றான 1862 கோடையில் பிரகடனத்தை அறிவிக்க களத்தில் ஒரு வெற்றிக்காக லிங்கன் காத்திருந்தார். போரின் முதல் ஆண்டில் ஒன்றியத்தின் இராணுவப் பின்னடைவுகள் லிங்கனை அகற்றப்பட வேண்டும் என்பவர்களுடைய நிலைப்பாடான கூட்டமைப்பை அடிமை முறையை அழிக்காமல் தோற்கடிக்க முடியாது என்பதற்கு வெற்றிகொண்டுவிட்டது. “நாம் அடிமைகளை விடுவிக்க வேண்டும், அல்லது நாமே அடக்கப்பட்டுவிடுவோம்” என்று அவர் முடித்தார்.

ஓரளவிற்கு அடிமைகளே இப்பிரச்சினையை முன்னிறுத்தினர். பிரகடனத்தின் மற்ற விதிகளில் இருந்து இது தெளிவாகிறது. ஒன்றியத்தின் இராணுவம் எங்கு நகர்ந்தாலும், அடிமைகள் அதன் பிரசன்னத்தை பயன்படுத்தி ஓடிவிட்டனர். தொழிலாளர் பிரிவு அகன்றுபோகத்தொடங்கியது முழுத் தெற்கின் பொருளாதாரத்தையும் அச்சுறுத்தியது. எனவே ஆவணம் ஒன்றியத் தளபதிகள் கிளர்ச்சிப் பகுதியில் உள்ள எஜமானர்களிடம் தப்பியோடிய அடிமைகளை திருப்பிக் கொடுத்தலைத் தடுத்தது. இதனால் காங்கிரஸ் முன்னதாக இயற்றியிருந்த பறிமுதல் சட்டங்கள் உறுதியாயின.

அடிமை ஒழிப்பு பிரகடனம் போரின் இராணுவ நடைமுறையை மற்றொரு முக்கியமான வகையில் மாற்றியது. இது லிங்கன், தளபதிகள் ஜோர்ஜ் மக்கிளெல்லென் போன்றவர்களை அகற்றி, பதவிக் குறைப்பு செய்ததுடன் இணைந்து வந்தது. இவர்கள் தெற்குடன் சமரச நிலையில் போரிட்டனர், உலிசிஸ் கிரான்ட், பிலிப் ஷெரிடன் மற்றும் வில்லியம் டெக்யூம்சே ஷேர்மன் போன்றோர் உயரிடத்தைப் பெற அரங்கும் அமைத்தது. இதன் வேறுபாடு மிகவும் குறிப்பிடத் தக்கது ஆகும். தெற்கே உள்ள பண்ணை உரிமையாளர்களிடம் மக்கிளெல்லென் அவர்கள் தங்கள் சொத்துக்கள் பற்றியோ அடிமைகளைப் பற்றியோ பயப்படத் தேவையில்லை என்று குறிப்புக்கள் கொடுத்தார்: ஷேர்மன் அவருடைய நோக்கம் “ஜோர்ஜியா கூச்சலிட வேண்டும்” என்றார்.

இப்பிரகடனம் மகத்தான சர்வதேச தாக்கங்களையும் கொண்டிருந்தது. செப்டம்பர் 17ம் திகதி ஆன்டைடம் போரில் லீயின் இராணுவம் தோற்கடிக்கப்பட்டது தற்காலிகமாக பிரித்தானியா அல்லது பிரான்ஸ் தென்புறத்தின் சார்பில் தலையீடு செய்யும் ஆபத்தைத் தவிர்த்தது. (அப்போரின் காலையில் பிரித்தானியப் பிரதம மந்திரி பாமெர்ஸ்டன் பிரபு தன்னுடைய வெளியுறவு மந்திரிக்கு மோதலில் மத்தியஸ்தம் கொடுக்கும் நேரம் வந்துவிட்டது, “அதையொட்டி கூட்டமைப்பிற்கு அங்கீகாரம் கொடுக்கும் நேரம்” வந்துவிட்டது என்று ஒரு குறிப்பை அனுப்பியிருந்தார். பிரித்தானிய, பிரெஞ்சு ஆளும் வர்க்கங்கள் அதுதான் வெற்றி பெற வேண்டும் என விரும்பியிருந்தன.)

ஆனால் ஆன்டைடமிற்கு ஐந்து நாட்கள் கழித்து இறுதியில் வெளியிடப்பட்ட அடிமை ஒழிப்பு பிரகடனம் பிரான்ஸ் அல்லது பிரித்தானிய தெற்குச் சார்பில் பகிரங்கமாகத் தலையிடுவதை அரசியல்ரீதியாக இயலாததாக்கிவிட்டது. அதே நேரத்தில் ஒன்றியத்தின் குறிக்கோளை ஐரோப்பிய தொழிலாளர் வர்க்கத்தின் குறிக்கோளாக்கியது.

ஒன்றியத்திற்கு ஆதரவாக இங்கிலாந்தில் பாரிய ஆர்ப்பாட்டங்கள் நடைபெற்றன. ஒன்றிய முற்றுகை “பஞ்சுப் பஞ்சத்தை” யும் பிரித்தானிய ஆலைகளில் பாரிய வேலையின்மையையும் கொண்டுவந்திருந்தும், இந்த ஆதரவு நிலவியது. அந்த ஆர்ப்பாட்டங்களில் ஒன்றில் ஒரு தீர்மானம் “மான்செஸ்டர் உழைக்கும் மக்களால்” இயற்றப்பட்டது; அது விடுதலை “ஆபிரகாம் லிங்கனின் பெயரை பெருமிதப்படுத்தவும், பெருமதிப்பிற்கு உட்படுத்தவும் வருங்காலத்தில் செய்யும்” என்று அறிவித்தது.

“மான்செஸ்டர் மற்றும் ஐரோப்பா முழுவதிலும் உழைக்கும் மக்கள் பெற்றுள்ள துன்பங்கள் இந்நெருக்கடியைப் பொறுத்துக் கொள்ளுவதால் ஏற்பட்டுள்ளது” என்பதை ஒப்புக் கொண்டு லிங்கன் விரைவில் ஒரு கடிதப் பதிலை எழுதினார். “மான்செஸ்டர் தொழிலாளர்களுக்கு அவர்களுடைய இப்பிரச்சினையில் உறுதியான நிலைப்பாடு குறித்து” லிங்கன் நன்றி தெரிவித்தார். இக்கடிதம் பிரித்தானியாவில் உள்ள அமெரிக்கத் தூதர் சார்ல்ஸ் பிரான்ஸிஸ் ஆடம்ஸினால் கொடுக்கப்பட்டது; இவர் அமெரிக்கக் குடியரசு நிறுவிய தந்தைகளில் ஒருவரான ஜோன் ஆடம்ஸின் பேரன் ஆவார்.

அடிமை ஒழிப்பு பிரகடனம் “அமெரிக்க வரலாற்றில் ஒன்றியம் நிறுவப்பட்ட காலத்தில் இருந்து மிக முக்கியமான ஆவணம் ஆகும்” என்று மார்க்ஸ் பொருத்தமாகக் கூறினார். லிங்கனே இன்னும் புகழ்பெற்ற வகையில் கெட்டிஸ்பெர்க் உரையில் மீண்டும் மீண்டும் அமெரிக்கக் குடியரசின் நிறுவன ஆவணமான சுதந்திரப் பிரகடனத்தையும் அதில் இருந்த புரட்சிகரக் கருத்தான “அனைத்து மக்களும் சமமாகப் படைக்கப்பட்டுள்ளனர்” என்பதையும் மேற்கோளிட்டார்.

இச்சொற்களுக்கும் அடிமை முறை இருந்த நிலைப்பாட்டிற்கும் இடையே இருந்த முரண்பாடு புதிய குடியரசை பரிசோதனைக்கு உள்ளாக்கித் தவிர்க்கமுடியாமல் உள்நாட்டுப் போருக்கு இட்டுச் சென்றது. இரண்டாம் அமெரிக்கப் புரட்சி 1863ல் லிங்கன் கூறியது போல் “சுதந்திரத்தின் ஒரு புதிய பிறப்பாகும்.”

அடிமை ஒழிப்பு பிரகடனத்தில் உள்ளடங்கியிருக்கும் புரட்சிகர ஜனநாயகக் கருத்தாக்கங்களுக்கும் வர்க்கச் சுரண்டலை அடித்தளமாக உடைய ஒரு சமூகப் பொருளாதார முறைக்கும் இடையே அடித்தளத்தில் இருந்த முரண்பாடு விரைவில் உள்நாட்டுப் போரின் முடிவில் வெளிப்பட்டது. 1877ல் குடியரசுக் கட்சி தெற்கில் மறு கட்டமைப்பை நிறுத்த ஒப்புக் கொண்டு, அரசியல் அதிகாரத்தை பழைய நிலப் பண்ணைப் பிரபுக்களின் வாரிசுகளிடம் ஒப்படைத்தது. அதே ஆண்டு குடியரசு மற்றும் ஜனநாயகக் கட்சி அதிகாரிகள் துருப்புக்களையும் பொலிசாரையும் ஒருங்கிணைத்து நாடு முழுவதும் பெரும் இரயில் வேலைநிறுத்தத்தில் எழுச்சி செய்த தொழிலாளர்கள் மீது துப்பாக்கிச்சூடு நடத்தினர்.

அமெரிக்க ஆளும் வர்க்கம் நீண்ட காலமாக அமெரிக்கப் புரட்சி மற்றும் உள்நாட்டுப்போரின் புரட்சிகர ஜனநாயக மரபுகளை மிதித்து வருகிறது. இன்று, தன்னுடைய சொத்துக்களைப் பெருக்கவும் செல்வந்தர்களுக்கும் ஏழைகளுக்கும் இடையே உள்ள பிளவை அதிகரிக்கும் வகையில் சுரண்டல், அடக்குமுறை ஆகியவற்றை அது கையாள்கையில், முதலாளித்துவம் அதன் பேராசை மற்றும் திமிர்த்தனத்தில் பழைய அடிமைமுறை எஜமானர்கள் உயரடுக்கிற்கு வியத்தகு வரையில் ஒத்திருக்கிறது.

ஒபாமாவிற்கும் ரோம்னிக்கும் இடையே நடக்கும் தற்போதைய ஜனாதிபதிப் போட்டியை கவனித்தால், அது ஆளும் வர்க்கம் சமத்துவத்திற்கு எதிராகக் கொண்டிருக்கும் இயல்பான வெறுப்பைக் காட்டுகின்றது. பெரும் செல்வம் படைத்த நிதிய ஒட்டுண்ணியான ரோம்னி மக்களில் “47 சதவிகிதத்தினரை” அவர்கள் “சுகாதாரப் பாதுகாப்பு, உணவு, வீடு ஆகியவற்றிற்கு உரிமை உண்டு” என்று நம்புவதற்காக எள்ளி நகையாடுகிறார். முற்றிலும் புதிய, வெளிக்கருத்தான “செல்வம் மறுபங்கிடப்படல்” என்பதை அமெரிக்க அரசியலில் நுழைப்பதாகக் கருதி அதற்காக ஒபாமாவைத் தாக்குகிறார். உண்மையில் டிரில்லியன் கணக்கான டாலர்கள் செல்வத்தை தொழிலாளர் வர்க்கத்திடம் இருந்து நிதிய உயரடுக்கிற்கு மேலே மறுபங்கீடு செய்துள்ள ஒபாமா மறைமுகமாக தொழிலாள வர்க்கம், வறியவர்கள் ஆகியோருக்கு ஆதரவு கொடுக்கும் மறுபங்கீட்டுக் கொள்கைகளுக்கு எந்த ஆதரவும் இல்லை என்று உறுதி கூறுகிறார்.

“மறுபங்கீடு” மேலிருந்து கீழாக என்னும் கூற்று அமெரிக்க வரலாறு, கலாச்சாரம் ஆகியவற்றில் முற்றிலும் இல்லாத ஒன்றும் மற்றும் இது அறியாமையில் கூறப்படுவதும், தவறும் ஆகும். அடிமை ஒழிப்பு பிரகடனம் உலக வரலாற்றில் ரஷ்ய புரட்சிக்கு முன் தனியார் சொத்துக்கள் மிக அதிகமான அளவில் பறிக்கப்பட்டதைத்தான் அறிவித்தது.

அமெரிக்க நிதியப் பிரபுத்துவம், அரசியல் கட்சிகள் இரண்டையும் மேலாதிக்கம் கொண்டுள்ளதுடன் அரசாங்கத்தின் ஒவ்வொரு நிறுவனத்தையும் கட்டுப்பாட்டிற்குள் கொண்டிருக்கிறது. பழைய அடிமைச் சக்தியைப் போல், அது தானாக, தன்னியல்பாக வரலாற்று அரங்கில் இருந்து நகராது. அடிமை வத்திருக்கும் உயரடுக்கை ஒழிப்பதற்கு அடிமைகள் விடுவிக்கப்பட வேண்டும் என ஆயிற்று. அதேபோல் நிதியப் பிரபுத்தவத்தின் சக்தியை அழிப்பதற்கு முதலிலும் முக்கியமானதுமாக தொழிலாள வர்க்கத்தின் அரசியல் விடுதலை தேவைப்படுகிறது.

No comments:

Post a Comment